When it comes to the past, wherever truth matters, fakes abound. The creation, distortion, manipulation or reconstitution of information shapes our experience of the world at every level.

The growing sophistication of technology seems to have amplified rather than solved the problem by providing new techniques for faking everything, from currency through to identity. Such nefarious uses of technology have fast outstripped developments in authentication.

While scientific procedures are increasingly used to authenticate artefacts, these techniques often fall short. As capable as they are of identifying modern fakes, they are unable to prove whether an object is authentic - they can only determine that they are not forgeries.

Telling ‘real’ from ‘fake’, ‘true’ from ‘false’ and ‘original’ from ‘copy’ is not simply a dilemma of modern information technology - seen, for example, in the recent rise of politicians invoking the phrase “fake news” as a rhetorical tool to undermine rival opponents - but a crisis of history.

From suspicion of oral histories among some historians to distrust of the details of eyewitness testimony in the legal sphere, we're acutely aware of this crisis every time we try to exemplify and affirm ‘facts’ about the world.

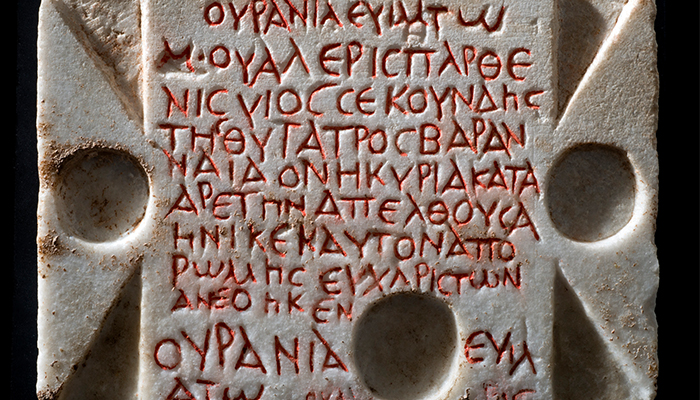

A Greek inscription in the Museum of Ancient Cultures at Macquarie University. Several aspects of its script and language suggest it may be a modern forgery. Credit: Effy Alexakis.

Fake artefacts are often created for financial gain - within the last month, the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC has taken five fragments of what they believed were Dead Sea Scrolls off their displays, after scientific tests and observation of their text and script revealed they were modern creations.

As fragments of Jewish and Christian scripture command huge prices on the antiquities market, the motivating for forging them is clear.

In many cases, there are other motives. Some represent calculated attempts to re-engineer history, such as the papyri forged by master forger Constantine Simonides in the mid-19th Century which re-wrote the history of Greece, Egypt and the New Testament.

Some promote a certain point of view, such as the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” first brought to light in 2012 which implied some early Christians believed Jesus was married.

Others are intended to damage the credibility of opponents, such as the alleged translation of the Gospel of Thomas into Demotic Egyptian "discovered" by a fictional researcher, Batson D. Sealing, and sent to the Department of Egyptology at Oxford in an attempt to embarrass researchers there.

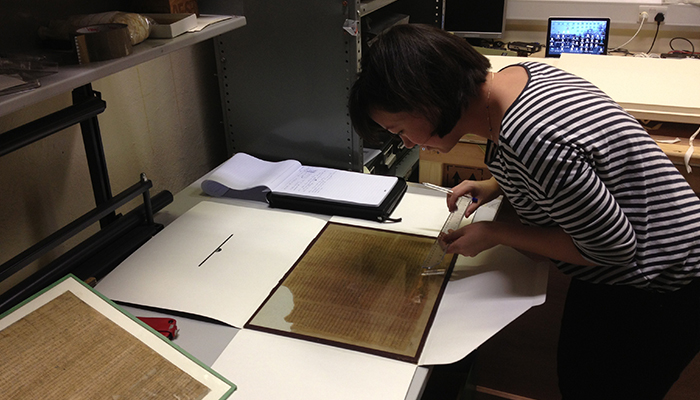

Dr Yuen-Collingridge examining fake papyri by the forger Constantine Simonides in the World Museum Liverpool. Credit: Malcolm Choat.

Along with our collaborator at the University of Heidelberg, Dr Rodney Ast, we are investigating fake papyrus manuscripts allegedly from ancient Egypt as part of the Australian Research Council-funded project “Forging Antiquity: Authenticity, forgery, and fake papyri”.

This project focuses on applying the study of script, language and history to the analysis of fakes in order to understand what knowledge enables their construction and what knowledge challenges it. The team also researches the persona of forgers and the communities they infiltrate, so as to capture the motivations and environments that give rise to forgeries.

It is for this reason that the team is focusing on Simonides, who has left a corpus of more than 30 fake papyri in Liverpool and an archive of hundreds of letters and documents in London. These have allowed us to uncover a fuller picture of his plan to claim a central role for Greek culture and wisdom in historical events, as diverse as the early development of the New Testament to the modern decipherment of hieroglyphs.

- Review: Rome City+Empire at the National Museum of Australia

- How Assassin's Creed triggered a world-first Egyptian hieroglyphics decoder

If museums contained only excavated objects, fakes would be far less common. Some have estimated that as many as 20% of the art in museums and galleries around the world is fake. In some collections, it is much higher: one report estimated 96% of the artefacts in the Mexican Museum in San Francisco were either certainly or possibly forgeries.

While numbers of Australian collections are unknown, it has been estimated that about 10% of the art sold in Australia is fake and it is certain that every collection contains forgeries. The trade in items which have no record of their provenance (collection history) or provenience (where they were found) makes fakes far easier to sell.

Assoc Prof Choat has studied dozens of Constantine Simonides' fake papyri. Credit: Malcolm Choat.

The black and "grey" market for antiquities is sustained by looting, which has reached endemic proportions in the Middle East and other conflict zones in recent years. The Museum of the Bible in Washington DC was recently forced to forfeit nearly 4,000 cuneiform tablets which were proved to have been illegally acquired from Iraq, and looted objects from Syria, such as a large mosaic of Heracles, have been confiscated in the US.

Another hotspot for looted antiquities is India - recent investigations undertaken by the Art Gallery of South Australia have revealed that a bronze statue of Shiva acquired by the gallery in 2001 for more than $400,000 was stolen from a temple in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu sometime in the 1970s.

Cases such as these underline the critical nature of research into the collection history of items before they are bought and sold, and the importance of an ethical approach to the collection of ancient objects.