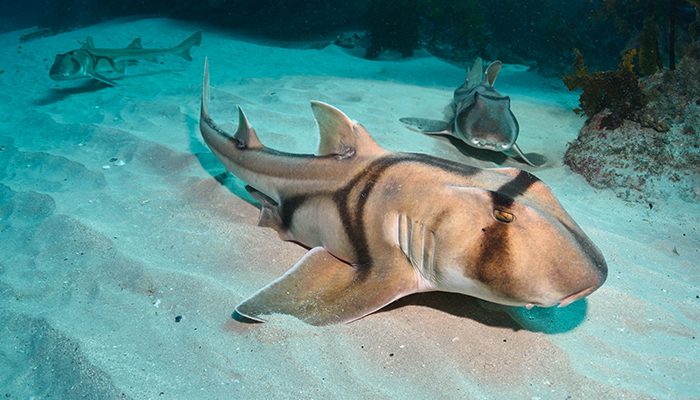

There are about 500 recognised species of shark worldwide and Australia is surrounded by a large amount of water, so we've got lots of different species of sharks but most of them are completely harmless to humans.

The concerning and sadly often fatal attacks on surfers and swimmers are attributed to three main culprits and that's white sharks, tiger sharks and bull sharks.

We really don't understand why sharks sometimes bite humans. It’s a very rare event, so that in itself tells you something. We often go in the water and there are sharks there, but we don't realise it. Attacks are extremely rare and people are rarely consumed by sharks.

A shark is capable of eating someone if they wanted to but it often doesn’t, which suggests we’re not considered prey and certainly not targeted, so that should allay a lot of fears.

Mistaken identity

As white sharks get bigger, between about two to three metres, they change their diet. They stop predominantly eating fish and start to include things like seals and sea lions in their diet.

From the deep: A shark will investigate and might just do an exploratory bite before leaving their victim alone, says Professor Hart.

From the perspective of a shark down below and looking up, whether it’s a seal or a sea lion swimming on the surface of the water or someone paddling on a surfboard or swimming along, these black silhouettes on the surface could look quite similar.

We’ve researched how similar those things can appear, based on what we know about the visual system of white sharks. Water can often be murky, so that's a complicating factor, making it harder for a shark to detect and identify objects beyond a few metres.

We also know that sharks are completely colour blind. They also have poor visual acuity – in other words, they can't see as much detail in an image as we can. It’s like someone who is short-sighted taking their glasses off.

Perhaps once they’ve had a bite of a surfboard or human they go, well hang on, this doesn’t feel or taste right, and then go away.

If you imagine a black and white and slightly blurry image, that's what a shark sees compared to humans. So the shark will go and investigate and they might just do an exploratory bite, but because it’s a white shark and they’ve got very big teeth and powerful jaws, it’s potentially going to do damage to people.

Obviously it's a bit chaotic when that type of event happens. Someone might start bleeding a lot. They may start panicking and thrashing around in the water. They may choose to fight back against the shark. There are things which may cause the shark to come back or go away.

- One in five people believe fake news about COVID-19: new study

- Bad behaviour at work: Whose responsibility is it?

The numbers would suggest that in general the shark leaves them alone after the initial bite and often people manage to get out of the water, which comes back to this idea that sharks are not really targeting humans.

Sharks have other sensory systems that they use close up – such as taste and electroreception – and perhaps once they’ve had a bite of a surfboard or human, they go, well hang on, this doesn’t feel or taste right, I’m not getting the right cues off this, and then go away.

Lighting the way for sharks

Our research, funded by the Australian Research Council as part of a project with Taronga Zoo, the NSW Department of Primary Industries, Flinders University, the University of Western Australia and Oceans Research in South Africa, has concentrated on sharks’ sensory systems and trying to understand how they perceive the world around them.

Great white repellent: Research by Professor Nathan Hart (pictured) and colleagues is looking at the possibility of putting lights on surboards to deter sharks.

It's trying to use what we know about shark visual systems to come up with shark deterrents. As part of this research, we're putting lights on the bottom of seal decoys to try and stop white sharks attacking those decoys, with a view to putting lights on surfboards and other water craft.

In reality, the risks of a shark attack are extremely low. There are lots of other activities that are far higher risk – including drowning or having a car accident on the way to the beach.

It’s natural to ask questions, but we have to remember you have got to be really unlucky to get bitten by a shark. People should continue doing what they love and accept that any time you go in the ocean, there's a certain risk of misadventure.

Professor Nathan Hart is Head of the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University.

* This story was first published on May 19, 2021.