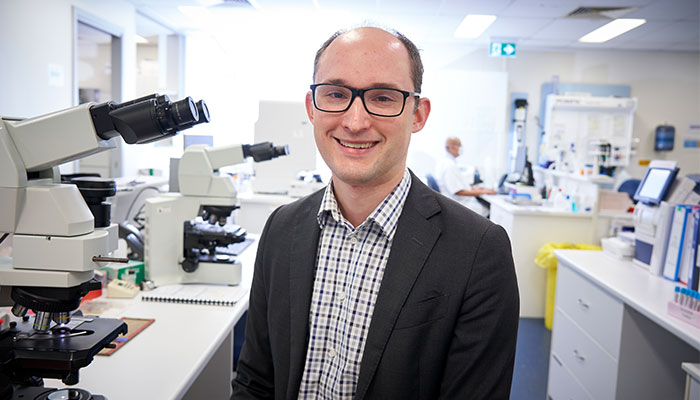

Teacher: Dr John Turchini is a clinical senior lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, where he teaches pathology, histology and anatomy. He is also a consulting pathologist at Douglass Hanly Moir Pathology. His special interests include endocrine pathology, neuropathology, pulmonary pathology, and gastrointestinal pathology.

Top teacher: Students say Dr John Turchini, pictured, is highly skilled at keeping his classes engaging by demonstrating how lab skills translate to a clinical setting. Image credit: Tim Robinson.

Groundwork: As a student, John was inspired to train in histopathology after a term at Concord Repatriation General Hospital. He practised clinical medicine at Hornsby and Manly hospitals and histopathology at Royal North Shore Hospital, with terms at the Department of Forensic Medicine and the Department of Neuropathology at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

Gold stars: Recipient of the 2021 Vice Chancellor's Learning and Teaching Student-Nominated Award. Recipient of the 2015 Registrar Teaching Award, Royal North Shore Hospital.

What students say about him: “Dr Turchini’s teaching in the lab is simply unparalleled. He goes straight to the point and manages to make it interesting by showing you the clinical application.”

“I have never been this excited and engaged in a prac … you will be amazed how much you learn because of its engaging delivery.”

What John says:

If you understand pathology, you understand how disease works. And therefore, in theory, you understand medicine. Pathology appeals to me because it is the last word in diagnosis. You’ve got a jigsaw puzzle and there’s one piece missing, and the pathologist often has that one piece.

As a pathologist, the wow moments are the diagnoses that don’t come along very often: when everyone's expecting diagnosis A and it turns out to be diagnosis B. You make the phone call to the clinician and say, well, actually, the patient has a fungal disease rather than the cancer you thought he had.

Pathology is not viewed as a glamorous specialty. Which might explain why there’s a worldwide shortage of pathologists. It is often seen as a dry subject. People think we are antisocial because we don’t see patients. Indeed, some students are surprised to learn that a pathologist is actually a doctor! In reality, we have more contact with our colleagues, pathologists and clinicians than many other specialities.

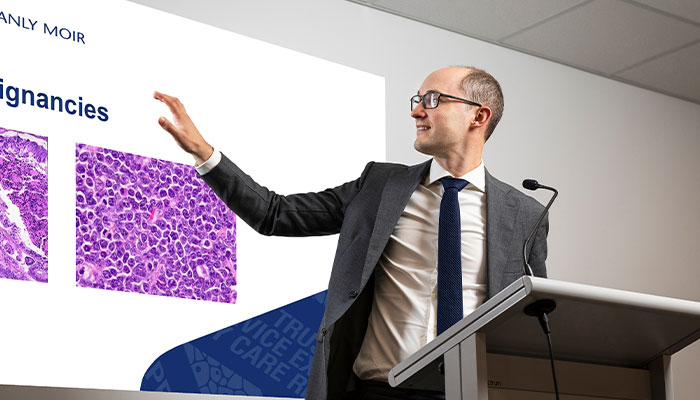

What makes a subject dry is not necessarily the content, but the way it’s delivered. My goal is to transform a ‘dry’ subject into an interesting, engaging and memorable topic. The trick is not to lecture. I don't like to stand up the front and deliver lots of information. I prefer to have a dialogue with students, to quiz them - to assist them to get to the answer by asking a new question, rather than just telling them the answer.

Engaging: Dr John Turchini's goal is to transform a 'dry' subject into a memorable topic.

In high school at Barker College [on Sydney’s North Shore] my Year 9 maths teacher turned a very esoteric subject into something I understood. But it was my Year 11 biology teacher who made me recognise medicine as a potential career. He was fun, laid back and relaxed. I really, really enjoyed that year. I do think your high school teachers make a big impact on you.

I try to make university classes fun. Medical students tend to be quite competitive. A little bit of friendly competition helps. I might break students up into teams or establish a game show scenario whereby ‘contestants’ have to answer questions about different cancers. Or students might need to work as a team to investigate a patient’s presentation with different pathology tests. Students need to learn that a poor choice or a bad decision can harm a patient. Gamification can help them understand just how choices matter.

It's important to let students know they are in a safe space: that they won’t be judged or made to feel stupid if they don’t know the answer to a question. I might suggest they nominate a friend in the class to answer a question they can’t answer. That can be fun. But at the same time, too, I like students to leave the classroom feeling that they know more than they did when they arrived.

There has been a big shift in the way medicine is taught. Traditionally, you’d give an hour-long lecture in a big theatre on a particular topic which would have no clinical context. A student was expected to go away and read the textbook, see a patient down the track, and apply what they have learnt.

There has been a big shift in the way medicine is taught.

Medicine today is more about a small group setting. There will be a high-quality teacher-student ratio to ensure everyone understands the content. The content itself should have relevance to how people are going to be using this information when they are doctors.

Students in the 21st century need to be able to critically analyse material. They need to recognise what is a good and reliable resource and what isn't. What I want students to learn is never to just type something into Google and think the first result and the most common result must be the answer. Similarly, if you’re reading material, you need to be able to determine whether a study was done in a manner that is accurate, that is reliable.

The greatest impact of COVID-19 was on practical work. Anatomy especially. Teaching anatomy is something that really has to be hands-on because it’s all about relationships.It’s not just about what a body part is called, it’s about what it connects to, how is it used, what relevance does it have? Can the student think of a setting in which a patient might not be able to do what that body part requires? It’s about painting a clinical picture. Without having a cadaver in front of you, it’s very difficult.

How would I like my students to remember me? I'd like them to think that I really cared about them. I want them to understand pathology, anatomy, and histology, and to be good at whatever specialty they choose. When they come to fill in the pathology or radiology request form, I want them to know exactly what to write.

Medicine is a subject in which you never stop learning. I am always looking for the ‘aha’ moment; that look of recognition on a student’s face when they have grasped a concept for the first time. Teaching is also not a one-way street. Teachers can also learn from their students. To be asked a question that you have never considered yourself is a positive, rewarding thing as you also learn from the process.