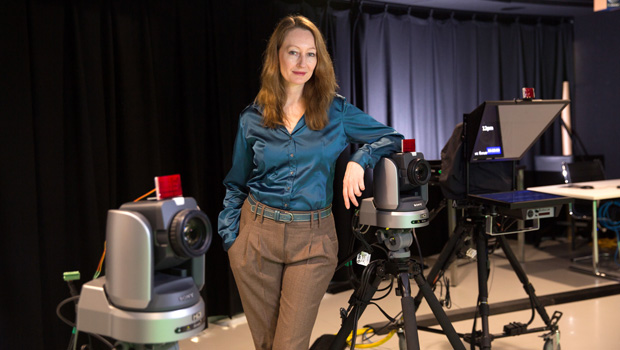

Professor Nicole Anderson: critical thought is more important than ever.

Fake news. Alternative facts. Fake massacres.

When Kellyanne Conway, a key advisor to US President Donald Trump, talked about the Bowling Green Massacre she claimed terrorists mounted in New York, the ‘non-fake’ facts tell us it never happened.

Conway later recanted her version of the non-events to CNN but also said she thought the Trump administration was besieged by media bias and said: “I think there are some reports everywhere, in print, on TV in radio, in conversation that are not well-researched and that are sometimes based on falsehoods”.

Getting the facts wrong

I asked my colleague Professor Catharine Lumby, a senior researcher in our department who worked as a print and television journalist for two decades, what she made of Conway’s claims about mainstream media reporting.

She responded: “There is no doubt that the mainstream media often gets their facts wrong. More importantly, all journalists are human – they bring their own opinions to stories however hard they try to eliminate bias”.

What she is saying, in a nutshell, is that there has never been something we might call objective news. Yet it’s also true that we are now living in a world where the internet and social media have made it far more likely that conspiracy theories and genuine untruths spread rapidly and distort democracy.

Now everyone’s a content producer

The rise of social media has democratised our conversations and the ability of anyone with access to the internet to produce and share their own opinions and media content. Yet there are also potential risks, in particular the risk that all opinions are treated as fact.

More than ever, we are living in a world where opinion and facts are often treated as equivalent. Hence the term, ‘alternative facts’.

In the academic sphere we are trained rigorously to make a distinction in the sciences and the humanities between opinion and argument, or our own opinions and what we find factually in our research. Naturally it rankles when our expertise is dismissed. Just ask climate change experts how they feel when decades of their research is wiped away by politicians who treat climate change as an inconvenient fact.

So where does that leave expert researchers? How do we respond to ‘alternative facts’?

Teachers and researchers push back

In my view it makes our job as teachers and researchers all the more important. By promoting our research in the public domain and by educating the next generation to think critically and evaluate the information they receive, we are able to push back against the tide of personal opinion dressed as fact.

A large part of that is ensuring that all our students are given the skills to think in a discerning way about the deluge of information they will encounter outside the university walls.

It also gives academics an urgent call to action to communicate their research as widely as possible and to engage in public debates. Now is not the time to sit back. We need to speak out and disseminate what we know.

The doom and gloom we read about when it comes to traditional media jobs – the allegations of ‘fake news’, the jeremiads about young people no longer caring about the Fourth Estate, the failing business models of traditional media – are all depressing.

Yet, at Macquarie we are highly engaged in producing bright young, ethically engaged graduates who are going to be part of the generation who turn that tide. I am confident the tide will turn.

Professor Nicole Anderson is Head of the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies.