One in six surgical instruments accidentally left inside a patient were not discovered for more than six months, with one sponge undetected for 18 months, Macquarie University research has found.

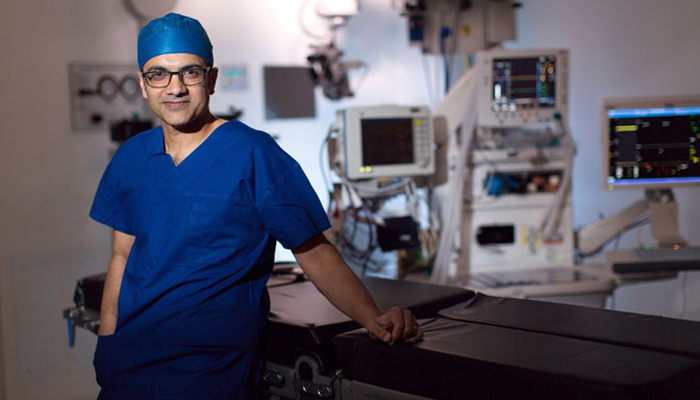

Led by Hon. Associate Professor Peter Hibbert, from the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University, the research was based on analysis of 31 detailed investigations. The incidents occurred over five years across hospitals in Victoria.

Almost one-quarter of the retained surgical items were discovered on the day of the procedure. All but one of the cases had to have a second surgery due to the mistake.

Around two-thirds of foreign bodies were sponges, drain tubes and vascular devices. There was also a surgical instrument, a cochlear implant stainless steel template and guide-wires.

The research has delivered some practical and immediate solutions to the problem of incidents of surgical instruments wrongly left inside patients.

Although the study numbers were low, the detailed investigations conducted by the hospitals enabled the research team to develop quality recommendations.

“You’re analysing real events and that’s really useful,” says Hibbert, who conducts and teaches medical professionals how to correctly conduct these investigations.

“Most surgical teams manage these devices well. It was an opportunity to look at investigations into incidents that happen rarely, understand what happened and why and then share that in order to reduce further incidents happening again.”

Mistakes most common in abdominal surgery

To prevent leaving devices inside patients, surgical teams systematically count, or check off, the instruments used before, during and after a procedure.

Hibbert said the Victorian numbers mirrored the pattern of incidents across most developed health systems around the world, including in NSW. About 30 incidents occur every year across Australia.

The problem occurred most often in abdominal operations, but researchers found that no surgical specialty or procedure was immune; it also happened during post-operative care.

Injuries can include pain caused by the unwanted device pressing on a nerve or taking up space, perforations, bowel obstructions, sepsis or serious infections.

Of all 'sentinel events' – infrequent incidents usually resulting in serious harm to patients and commonly reflecting hospital deficiencies – those caused by retained surgical instruments are the second most common (after inpatient suicide).

“It can be a distressing event for patients,” Hibbert said. “These foreign bodies can cause pain, loss of function and infections. Left in for an extended time, people did re-present to emergency with serious pain and they had to be re-operated on.”

Some of the incidents included:

- A microvascular clamp accidentally left after a 10-hour surgery involving two teams (orthopedics and plastics) and three separate counts of devices for different components of the operation, compounded by short staffing with seven scrub nurses on personal leave and confusing handovers.

- A registrar left unsupervised to complete a surgical procedure without being familiar with the process for securing the drain, and no information about fixation on the drain packaging.

- An uncorrelated surgical instrument count not mentioned in the discharge summary, meaning a retained surgical pack was not considered as a possible explanation when the patient was subsequently admitted to the same hospital with abdominal pain.

Fatigue, noise needs management

The research has delivered some practical and immediate solutions to the problem of incidents of surgical instruments wrongly left inside patients. Managing fatigue, communication, noise and interruptions, especially in long or complex surgeries, can reduce wrong counts of devices.

One-quarter of left devices were related to post-surgical drain tubes, suggesting opportunities to improve their design and usage. Similarly, changes could be made to operating theatre set-up, for example in ensuring the whiteboard could be seen by all staff.

- The missing piece in finding a vaccine

- Oil tanks, driving prices into uncharted territory

- The coronavirus has changed work forever

“The majority of incidents don’t occur because clinicians are doing the wrong thing, but because of the complex system in which they work,” Hibbert says.

Based on the same data, the researchers previously won the Reizenstein Award for an in-depth report into the quality of health investigations over five years.

Hibbert commended the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services and Safer Care Victoria for their support of this research and urged hospitals to use the results to better understand these rare but distressing events and how to prevent them.

Associate Professor Peter Hibbert is a Program Manager at the Centre for Healthcare Resilience and Implementation Science, Australian Insititute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University.