Jim Battiscombe discovered he was HIV positive in 1990, and spent the first two years of his diagnosis caring for his partner Peter, who had been diagnosed at the same time but quickly developed full-blown AIDS.

Compassion and care: Victorian Aids Council volunteers in 1987 ... In the Eye of the Storm captures the experiences of volunteers who looked after AIDS sufferers in the 1980s and 1990s. Photo credit: Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

As Professsor Robert Reynolds, co-author of new book In the Eye of the Storm, recounts, Peter – who with Jim had first registered the existence of HIV/AIDS during a 1983 holiday together in San Francisco – became emaciated and desperately ashamed of his body.

“But Jim said, ‘Don’t be ashamed, I have never loved you more than I do now,’” says Reynolds, a historian who is currently the Associate Dean Research in the Faculty of Arts.

The story of Jim, who survives today - and who after Peter’s death became a volunteer whose work included reaching out to the isolated community of straight HIV-positive men - is one of 12 told by Reynolds and his co-authors.

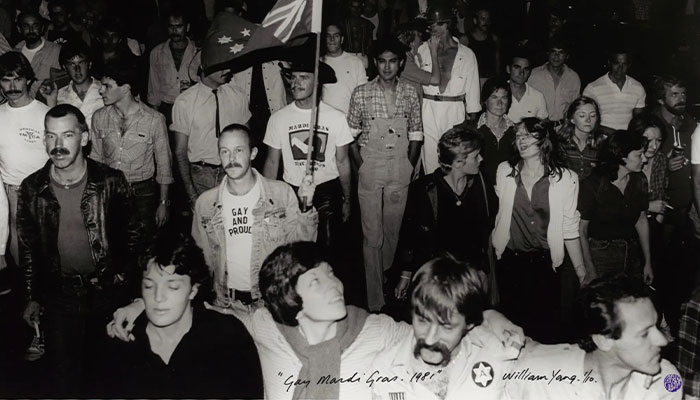

There was a short 10-year period of gay liberation before suddenly we were back into this context of sickness, illness, perversion and death.

As well as both HIV-positive and -negative gay men, the 12 interviewees include women and relatives of AIDS patients who stepped up at a time when the nation was gripped by terror and ignorance about the disease, and gay men bore the brunt.

“The AIDS epidemic was so potent because it set into an already existing shame about gay sexuality that many gay people would have felt growing up,” Reynolds says.

“Then there was a short 10-year period of gay liberation before suddenly we were back into this context of sickness, illness, perversion and death … it was a perfect cultural-medical storm.”

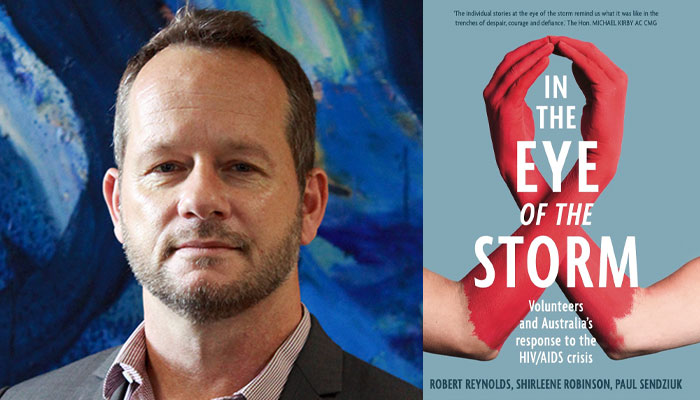

In The Eye of the Storm is Reynolds’ fourth book on post World War II gay life in Australia, but the first to delve deeply into HIV-AIDS.

“Primarily the book is a social history of the epidemic through the eyes of the volunteers,” Reynolds says.

Out and proud: The 1981 Sydney Gay Mardi Gras, before HIV/AIDS descended on the community after only a short 10 years of gay liberation. Photo credit: William Yang

“The thing is it is now very much history – It is 40 years in June since The New York Times first reported this strange affliction affecting gay men.

“It is not that the after-effects of AIDS don’t continue, and around the world there is still a desperate problem in some areas, but in terms of those crisis years they are definitely in the past in Australia.”

Reynolds says that hearing the volunteers’ stories is important because it presents for readers the nuts and bolts experience of the epidemic – including what it was like to care for people as they died in their homes.

“It is also about what it was like as an HIV-positive person to find a way through volunteering to make it easier to live with HIV yourself; and it also gave us the opportunity to speak to family members and bring their stories out.”

Enduring grief

In 1986, Trevor Williams was bedside in a Melbourne hospital during the last three weeks of his gay brother David’s life, and consequently became a volunteer carer for HIV-positive patients – his first client being a married man whose family insisted that his carers be heterosexual.

Breaking barriers: Princess Diana talks to AIDS patients in a London hospital in 1989 ... strong volunteer networks in Australia enabled AIDS patients to be cared for at home.

David was one of the early AIDS victims in Australia; the disease went on to claim more than 5000 lives during the crisis years, with deaths peaking in 1994 before the advent of effective anti-retroviral drugs saw AIDS cases plummet.

“Trevor spoke about the experience of being with his brother every day in hospital and holding his hand and he had a few flashbacks during the interview to being in the hospital ward – he loved his brother, and the grief he still felt for him came through,” Reynolds says.

“Trevor got to read the first draft of the chapter and to approve it but he has since died, and on his behalf we dedicated the chapter to his brother.”

The gay community was in some ways very well placed to respond – they had already been living and dealing with being marginalised.

Reynolds says that once it was understood that HIV/AIDS was a hard disease to transmit, more and more people were able to choose to die at home rather than in hospital, as David Williams had done, because of volunteers – some of them formal teams from AIDS councils, but also informal groups of friends and family.

“The volunteering came out of deep community friendships and networks,” Reynolds says

“In the previous 10 years and more before HIV-AIDS hit, there had been a long build-up of community organisations and gay networks and social life, so the gay community per se was in some ways very well placed to respond – they had already been living and dealing with being marginalised.”

Wider recognition

As volunteers dealt with repeated experiences of loss and a heavy workload of care, burnout was a big issue.

Social history: Professor Robert Reynolds (pictured) says the volunteers' stories expose the nuts and bolts experience of the epidemic.

“After a number of years a few of them had to take a break because of the emotional toll it took on them,” Reynolds says.

“On the other hand, a lot of them spoke about the benefits of volunteering, and the profound experience of accompanying people in their final weeks.

“Some talked about the sense of humour that they developed as a volunteer, which was often quite black, and how the volunteers through their camaraderie kept each other afloat.”

Reynolds says the contribution of HIV-AIDS volunteers – who also staffed needle exchanges and telephone help-lines, provided educational resources and served on management boards – has been well recognised within the gay community, but not so much beyond it.

“I wanted the book to put the work of the volunteers out there in the broader public arena,” he says.

“It would be lovely to have some sort of discreet monument to the volunteers of that period.

“For me, their stories show us the importance of human relationships, and the depth of these relationships at times of crisis.”

In the Eye of the Storm: Volunteers and Australia’s Response to the HIV/AIDS Crisis by Robert Reynolds, Shirleene Robinson and Paul Sendziuk, is published by UNSW Press.

Professor Robert Reynolds is Associate Dean Research in the Faculty of Arts