Modified commercial gaming headsets are being used to measure the impact of concussion on the brain in contact sports, with the potential for players to be diagnosed on the field.

VIDEO: Researcher Biana de Wit explains how her study on the sidelines will pinpoint players who should not go back on the field after a head knock. Videographer: Sophie Gidley.

Macquarie University cognitive scientists are carrying out the ground-breaking research on a dozen players from the GWS Giants as well as 60 players from the University's amateur Rugby League, Rugby Union and AFL men and women's teams.

Associate Professor Paul Sowman and Dr Bianca De Wit, from the Department of Cognitive Science, are looking at the electrical activity in "healthy brains" first to see how their visual systems respond.

In other words, athletes are asked to wear a set of VR goggles and watch a visual stimulus – black and white flashing lights – with the electrical activity in their brain then recorded via sensors on the headset.

"The brain is very neat in that if a healthy brain is presented with a visual stimulus that’s very regular, such as lights flashing at set intervals, the brain will adapt and fire at a similar rate," explains De Wit. "But if an athlete has a concussion, we expect the brain to be less responsive. Using technology, we can objectively test the integrity of the visual pathway after a concussion.

"We are also using technology to measure balance to get a real objective and more complete measure of what the effect of a concussion on the brain might be."

After the tackle, I got up and continued playing. It wasn't until the end of the game when the girls started singing our team song that I'd realised we'd won. I didn't even remember going ahead in the game.

The participants are being tracked throughout the season, with De Wit and Sowman making sure the effect of fatigue is taken into consideration.

The next major phase of their research will be to assess the brain activity of concussed players, "once we have an idea of what healthy brain activity in active athletes looks like".

Diagnosing a concussion – a type of brain injury that occurs from a knock to the head or body – is challenging because symptoms vary and can include a headache, nausea, confusion, sensitivity to light or balance problems.

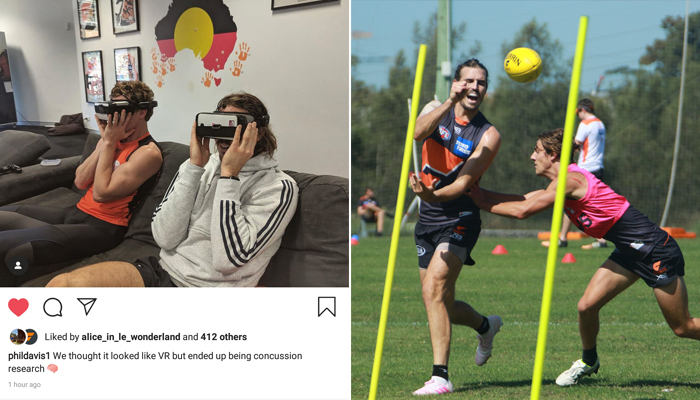

Backed by the pros: GWS Giants co-captain and defender Phil Davis shared a picture of himself taking part in the study with his 20,000+ followers on Instagram. Credit: @phildavis1/Instagram and GWS Giants.

A concussion is also diffcult to diagnose because symptoms are never the same between people or even in the same person.

"Our research is important because the impact of concussion has been underestimated for a really long time. If you have a broken arm or a wound to your leg, you can clearly see the damage but if you can’t really see the effects of a head knock then you never know when you’re truly hurt or when you’ve fully recovered," De Wit says.

Low price to pay?

She hopes the headset could eventually be used by medical professionals to diagnose players during a game, preventing them from being sent back onto the field to continue playing and risking serious injury.

The tech is portable and affordable, especially compared to laboratory-grade EEG (the technique – electroencephalography – that measures the brain’s electrical activity and is used by De Wit and Sowman). A headset costs just $1000 compared with roughly $50,000 for a typical research EEG.

Ground-breaking research: De Wit says the technology is crucial as it allows them to get an objective measure of what the effect of a concussion on the brain might be.

"Something really novel about our research is that we’re taking it out of the lab and onto the sports field," says De Wit.

"Most people don’t actually make it to the lab or the hospital for tests because they either carry on playing or don’t feel well and go home to lie down. Our research allows us to take the measurement right there on the sidelines."

The study is also ground-breaking in that it's assessing both men and women.

- Shut up and dribble! Should athletes speak their minds publicly?

- Is there a limit to human endurance?

- 'Fitbits' throw light on the secret lives of sharks

"The rise of female participation in contact sport is very important from our point of view, and we should pay attention to a potential difference between male and female athletes. We study brain activity in both male and females with the idea that we can compare the impact of a concussion to the brain between genders. That's something that we don't really know at the moment," De Wit adds.

Monique Le Motte, 24, captains the University's Division 2 women's AFL team and has sustained two concussions in the two years she's been playing the sport. She describes her most recent clash earlier this year as "really scary" after she suffered memory loss and struggled to remember the second half of the game.

Touchline technology: The innovative study is using low-cost equipment on the sports field rather than inside a lab.

"After the tackle, I got up and continued playing but I was a bit dazed and confused. It wasn't until the end of the game when the girls started singing our team song that I'd realised we'd won. I didn't even remember going ahead in the game," Monique, a physiotherapist, says.

"To be able to have something on the sideline which can tell you that you're concussed is a game-changer for players like me. A brain injury like that can be really serious and it's important that players are protected."

There has been growing concern in Australia, and internationally, about the possible long-term health risks for athletes. In June, it made news headlines once again after Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) - a disease linked to repeated concussions in American sport - was identified in the brains of two former Australian rugby league players.

And it’s not just a risk associated with contact sports - Australian batsman Steve Smith missed out on the third Ashes Test due to a delayed concussion after being struck in the neck by a ball in the previous match.

Road to recovery: The length of time it takes to recover from a concussion can depend on players' symptoms and the severity of their injury.

"Through our research, we aim to improve how we diagnose concussion and to understand what it does to the brain because we don’t actually know a lot about it currently. You can’t necessarily see the damage unless there’s something major going on," De Wit says.

"There's been a lot of media coverage around the risks associated with contact sport but our research isn't about stopping players from playing. It's all about making it safer. It's making sure a player is pulled off the field, has a proper rest and doesn't get a secondary knock."

Dr Bianca De Wit is a lecturer at Macquarie University's Department of Cognitive Science with a research interest in sport-related concussion and will be teaching in Macquarie University's new Bachelor of Cognitive and Brain Sciences program.

Participants wanted:

Researchers are looking for retired professional players to take part in this study. To register your interest email bianca.dewit@mq.edu.au.