Over the last few weeks we have seen an increase in the coverage of professional sports men and women using their public profile to express their opinions on a variety of topics ranging from the national anthem to the lifestyle choices of others.

Risky business: Dr Keith Rathbone believes athletes should use their enormous influence for good despite the very real risk of a public backlash.

When society deems the protest ‘worthy’ we get behind the athletes whole-heartedly. However, when people take offence, watch out! (Just look at the furore triggered by now ex-Wallaby Israel Folau’s anti-gay Instagram post.)

So should athletes take the opportunity to express their views even if it means risking their careers? I believe they should.

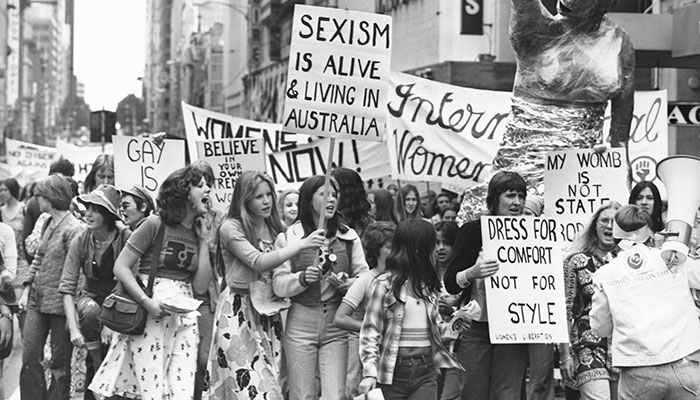

Folau’s sacking was widely debated and ultimately raised the perennial question of whether athletes should use their workplace to protest – an issue which intersects with a host of historical, legal, and philosophical complications. The number of athletic protests appears to be increasing, but sports protests have a long history and athletes have been among the first to take up social justice causes.

Politics and sport go back a long way

Many sports fans are more uncomfortable with athletes demonstrating politically because these protests naturally involve confrontation, division, risk, and sacrifice. Even so, athletes can and should protest for causes that they believe in and a growing number of athletes are doing so. Athletes occupy a special space in our public life and their notoriety gives them a megaphone to reach a large audience. Their authenticity ultimately provides their words added weight.

Athletes defend their right to express themselves politically in their workplace by pointing out that sports are inherently political.

We have had powerful displays of political protest in the sporting arena throughout history: Jewish sportsmen and women, including the Austrian national champion swimmer Ruth Langer, boycotted the Berlin Games in 1936; Australian Peter Norman joined John Carlos and Tommie Smith as they raised their fists in Mexico in 1968; and more recently, African-American football players, members of the French national soccer team, and Indigenous State of Origin footballers have ostentatiously refused to sing their national anthems in protest of the poor treatment of minorities in the US, France, and Australia.

Silence speaks 1000 words: Indigenous NRL Blues player Latrell Mitchell did not sing the national anthem at Brisbane's Suncorp Stadium at State of Origin I earlier this month as a cultural protest.

These brave athletes defend their right to express themselves politically in their workplace by pointing out that sports are inherently political. Corporations, governments, and religious organisations around the world have politicised sports for their own agendas for a long time: states made gym classes mandatory in order to prepare their populations for war and work; Hitler transformed the 1936 Olympics into a stage for propaganda; and the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a Cold War on the ice.

Shut up and dribble

For much of the 20th century, the men that organised athletic competition fought to keep it as a-political as possible. From its founding, the organisers of the modern Olympic Games have attempted to keep the Games pure of political interference and the Olympic Charter warns sportsmen and women that “no kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted”. Yet, we know that the Olympics excite our nationalist passions as cross-city rivalries can engender sectarian, ethnic and racial tension.

Not interested: US Fox News commentator Laura Ingram famously told basketball legend Lebron James to bounce the ball rather than air his political views.

Sports are political whether we like it or not, but the call to keep sports and politics separate is still pervasive. In 2018, when the American basketball star Lebron James, called some of President Trump’s policies “scary and laughable,” the Fox News commentator Laura Ingram said: “It's always unwise to seek political advice from someone who gets paid $100 million a year to bounce a ball” and told him to “shut up and dribble.”

There is no doubt that athletes retain the right to protest. Almost all Australians enjoy the right to protest in their place of work and few would argue that athletes should not be able to protest for better working conditions. Work place disputes are extremely common in sports: contract holdouts, industrial lockouts and strikes are but some, and they have been effective ways to argue for better treatment and pay for athletes. In 2015, the Matildas refused to play at a sold our tour of the United States and they won better salaries for themselves and their fellow players in the W-League as a result.

Sports are political whether we like it or not, but the call to keep sports and politics separate is still pervasive.

Damned if you do

Athletes who engage in political protest should know that it can, and probably will, end their career. No athlete knows the perils of political protest better than Colin Kaepernick who started the bend-the-knee protests in the NFL in 2016 to fight police violence against people of colour. Conservative politicians, including Donald Trump, called him unpatriotic and the NFL blacklisted him. Kaepernick sued the NFL for collusion and two years later, the two parties settled out of court. Neither disclosed an exact dollar amount, but the settlement was reportedly worth less than $10 million, much less than his annual salary as a veteran QB.

For some athletes, however, there can be a second act. In 2015, AFL fans booed two-time Brownlow Medalist Adam Goodes out of the league for his stand against racial intolerance. But this year, two documentaries, The Final Quarter and The Australian Dream were released telling Goodes’ side of the story. The AFL has since apologised to him.

- 'Sharenting' alert: the risks of sharing pics of your kids online

- Is there such a thing as too much exercise?

At the same time, we do not have to play Voltaire and defend every athlete’s activism. In 2017, I wrote an article defending the right of American football players to take a knee during the National Anthem. I would not defend Folau in the same way. His comments ultimately undermined the sport he claims to love and that is why I doubt that Folau will see the same rehabilitation of his reputation as Goodes.

There may be a double standard in supporting Kaepernick and Goodes, and not Folau, but ultimately, athletic protests involve the same risks as other political protests: some people will support you and other people will declaim you. I ask athletes to take the risk and protest anyway.

Dr Keith Rathbone is a lecturer in the Department of Modern History, Faculty of Arts, Macquarie University.