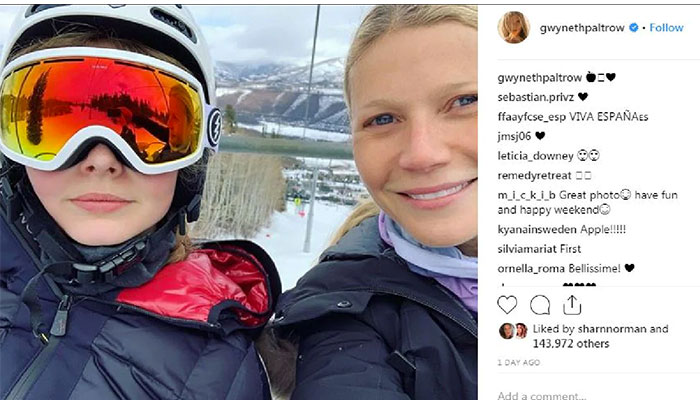

When Hollywood star Gwyneth Paltrow posted an Instagram selfie while skiing with her 14-year-old daughter Apple, she was quickly cut down by Apple, who commented – in full view of Paltrow’s 6 million followers: “Mom we have discussed this. You may not post anything without my consent.”

No consent, no photo, mom! Gwyneth Paltrow's daughter Apple chastised her celebrity mother on Instagram.

While Paltrow is not the first – or last – parent to be taken to task by their teenage offspring, Apple has chimed in on a curly and ongoing debate: to what extent is it OK for parents to post images, videos and blog posts about their children?

Social media is jam-packed with cute, quirky and sometimes embarrassing photos and videos of children posted by their parents, usually without their permission.

Researchers are now asking if the ‘sharenting’ trend is potentially a problem for children, as our digital footprints ripple wider and last seemingly forever. Screenshots and internet archive sites can perpetuate the life of social media dispatches long after posts or even accounts have been deleted – so fleeting childhood moments become a permanent record.

“We are moving into uncharted waters on the internet, and photos of their kids that parents might previously have stuck in an album or emailed to a relative, are now shared and made widely available on sites like Instagram,” says Dr Wayne Warburton, Associate Professor in Developmental Psychology at Macquarie University.

“This public sharing of childhood through photos also moves many of those strange competitions that happen between parents online, and we are starting to ask: what are the consequences?”

Sharing images can go beyond something that benefits the people involved, to something that may have unintentional or unexpected consequences.

Warburton points out that social media is neither inherently good nor bad. “There are lots of positive things that come about when parents share pictures. People feel good about themselves, they feel supported and validated and they feel connected with each other,” he says.

“But sharing images can go beyond something that benefits the people involved, to something that may have unintentional or unexpected consequences, both in the short and long term.”

The phenomenon of ‘digital kidnapping’ sees innocent images of children co-opted for advertising, used in fake social media profiles and even more disturbingly, re-purposed and discussed on paedophile image-sharing sites.

Living ‘idyllic childhoods’ vicariously

Dr Joanne Faulkner, who is an ARC Future Fellow in Macquarie University’s Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, says that there’s a deeper question around parents’ reasoning: “Why do parents – particularly mothers, culturally – feel driven to share their children’s images and life stories on the internet?”

Faulkner says that many parents appear to ‘package and commoditise’ their children, in order to present a particular image of themselves.

She argues that adults envisage childhood as an idyllic phase, separate from the responsibility of adulthood. “Some parents re-engage with this purer aspect of themselves vicariously through their children, and their children become a resource that lets them access this inner self.”

The problem with this, is that children are not seen as valid individuals in their own right, she says.

Children’s rights to a voice about their images

Associate Professor Warburton says parents mostly don’t even consider their child’s right to have a voice in how their image is disseminated online.

Private play: Parents are urged to consider the impact in later years of the images they share.

“I think young children do have those rights, and parents need to respect them,” he says.

“Some parents use their children’s images for the purposes of upward social comparison, where they want other people to envy them – in those instances, you're not thinking about the child at all, you’re focusing on your own status.”

He recommends that parents consider how each image they share could later impact their child.

“For me, the basic rule would be to communicate with your child, don’t do things without their permission and have a conversation about the long-term consequences.”

Those embarrassing photos of your kid picking his nose when he was six, could have devastating consequences.

Children also model their parents’ behaviour, often quite unconsciously, says Warburton. “If you’re thoughtful and cautious about what you post, you’re careful with what they are wearing in images and checking privacy settings and so on, that resonates,” he says.

In the longer term, these habits can be really important. “We all know that when you go for a job or someone wants to find out about you, they will first go online to find out about you, so those embarrassing photos of your kid picking his nose when he was six, could have devastating consequences.”

These habits could also later protect teenagers from making poor decisions about sharing nude images or explicit material, he adds.

Children’s privacy and the mummy blogger wars

Faulkner says the dilemma about posting images of children has been hotly debated recently, with Washington Post columnist Darlena Cunha writing last year about her own decision to stop writing about her children as they grew older.

- Faster, higher, emotionally stronger: risks help kids avoid anxiety

- How social media threatens our health

“She frames this in interesting terms: as children grow, she says that the parents’ sense of ownership of them lessens,” Faulkner explains.

Cunha wrote: “At first, they seem like simple extensions of ourselves, so that writing about them is like writing about us… We feel like we have a right to them, like our consent is their consent.”

But Faulkner points out that Cunha was mostly concerned about how her blogging and posting photos about her children could affect them as adults. “She is protecting their adult selves from their childhood selves, who she says have no sense of privacy and even want to be exhibited,” explains Faulkner.

It’s not about the child, but the adult they will become

Cunha, at least, is considering her kids’ wishes, Faulkner says. Another Washington Post columnist, Christie Tate, went against her own daughter’s wishes and kept writing about her family. Tate wrote that her daughter discovered images and stories about herself when she first googled her mother, and was furious, asking that past content be removed.

Roll model: If parents are cautious about what they post, their children in turn may pick up the habit.

“[Tate’s daughter] clearly is able to articulate a notion of privacy and her capacity to consent (or not) to an invasion of privacy,” says Faulkner. However, Tate refuses, arguing that writing about her own parenting experience is her own form of creative expression.

Tate prioritises her own desire to express herself through her child, over her child’s privacy, Faulkner says. “It goes beyond having boundary issues; Tate’s daughter is rendered as an externalisation of Tate’s inner world, rather than a person with her own inner world, or whose inner world has standing in a decision regarding whether or not to publicise it,” says Faulkner.

Cunha, on the other hand, sees privacy as something that she should now preserve so that her children can have this later, as adults, Faulkner says.

“In both cases, the value of the child’s inner life, or privacy, is discounted,” Faulkner says.

She believes parents need to regard children from their earliest infancy as having interests of their own, which potentially might be in conflict with their interests as a parent.

That way, parents would interact with their child in a way that takes for granted they have a right to consent, which then produces in children the capacity to consider their own interests and desires.

“If their privacy and subjectivity is respected from the first, children will attain decision-making competency far earlier than if they are not engaged with respectfully,” Faulkner argues.

Wayne Warburton is an Associate Professor in Developmental Psychology in the Department of Psychology.

Dr Joanne Faulkner is an ARC Research Fellow in the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies