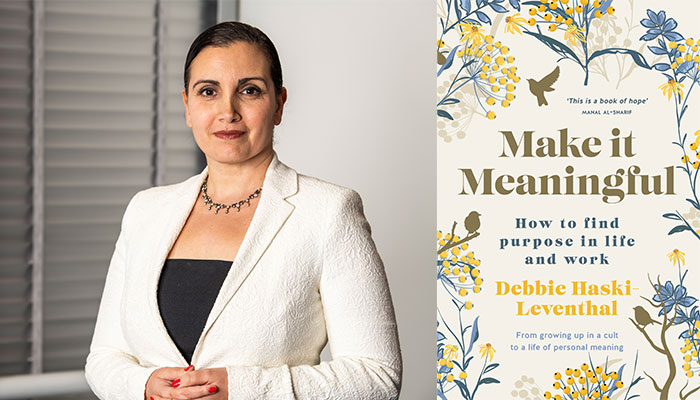

For Professor Debbie Haski-Leventhal, the key to finding true meaning in her life was making a difference to someone else’s. Tutoring “a sweet eight-year-old boy” from a disadvantaged background introduced to her the value of volunteering and, ultimately, the power of purpose.

Rescued: Author and Professor of Management Debbie Haski-Leventhal, pictured, says higher education saved her life.

In a new book, Make It Meaningful: How to Find Purpose in Life and Work, published this week by Simon and Schuster, Professor Haski-Leventhal shares her extraordinary life story to explore ideas of purpose, impact, values and resilience.

“Purpose is the goal that fills one’s life with a sense of meaningfulness,” says Professor Haski-Leventhal. “It is the destination that defines the quality of the journey.”

Finding that purpose, she adds, comes from harnessing three things: “The skills and capabilities that are your true talent, the things that are your passion and joy, and the ability to use those traits to make an impact.”

When she was five, family tragedy (the death of her older brother) prompted Professor Haski-Leventhal’s parents to join the Kabbalah Centre, a cult-like organisation based on Jewish mysticism. They immersed themselves in it unreservedly – from its rituals (rolling in the snow naked to purify their sins) to the beauty of belonging to something greater than themselves.

She left at 18 – after years of abuse and living in communes in three countries – devastated and isolated, searching for meaning in her life.

Learning as nourishment

At 20, Professor Haski-Leventhal moved from her home in Tel Aviv to Jerusalem to study philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Higher education, she says, saved her life.

To support herself, she tutored children from disadvantaged families, eventually managing a mentoring program and coordinating 1000 volunteers. Finding great reward in teaching others, she went on to study for a master’s degree in not-for-profit management and a PhD in volunteering.

Professor Haski-Leventhal migrated to Sydney in 2008 and three years later joined the staff at Macquarie University where she is today Professor of Management at Macquarie Business School, the MBA Course Director and the co-chair of MQ Inclusion.

Write thank-you letters to people who matter in your life. Even if they are not sent, the positive impact remains.

She has dedicated her career to studying the pro-social behaviour of individuals, mainly through volunteering, and the pro-social behaviour of organisations, focusing on corporate social responsibility, social entrepreneurship and purpose-driven organisations.

“I have seen how volunteering and purpose-driven organisations create a sense of meaningfulness for the people directly involved in such activities and for others,” she writes in her book.

Answers to the question of meaningfulness are internal rather than external, she maintains. “They’re a matter of personal awakening rather than alignment with an organised faith.

“We all need to choose who we want to be, define our individual and work purpose, and blaze our own trails. To begin, we may need to depart from some of the dogmas we used to hold dear, or from (mis)perceptions about ourselves, others, and the world.

“Some letting-go might need to precede the embrace of what is valuable and helpful for us and others.”

Seven essential ingredients for a meaningful life

Passion is like the fuel in the car and purpose is the vehicle’s direction, says Professor Haski-Leventhal. “These seven interconnected enablers make the car more efficient, with a better engine, wheels, and aerodynamic shape.” Its destination? Happiness, resilience, wellbeing, identity and kindness.

Her book details seven imperative enablers of meaning in life and at work:

- Connectedness: Hardwired to bond

Connectedness cannot be measured by the number of people we know, the strength of our networks or the number of followers. Connectedness can be solid even when we have only one strong relationship. High social connections have been shown to result in a 50 per cent increased chance of longevity, a stronger gene expression for immunity, lower rates of anxiety and depression and higher self-esteem.

The more we have solid connections with others, the better positioned we are to develop new relationships.

Connections: there's more to friendships than fun, says Professor Haski-Leventhal, with empathy at the heart of meaningful relationships.

Empathy is the cog without which there is no connectedness. We may have many ‘fun’ relationships, where we go out and laugh together, but to yield the benefits of genuine connectedness, we need to trust others and be vulnerable with them while allowing them to do the same.

Empathy requires active listening and compassion. It is not about walking a mile in someone else’s shoes; instead, we need to walk a mile with the other person, seeing and hearing them.

- Authenticity: Worthy of acceptance

Authenticity refers to an alignment between our actions and our values and desires despite external pressures to social conformity. Authenticity requires courage, which is not about never feeling any fear but overcoming that fear.

Authenticity is crucial to meaningfulness because we will not find our purpose and impact pretending to be someone we are not. We cannot understand our story, connecting the past, present, and future, if we no longer recognise ourselves. And most importantly, a shell of a person cannot cultivate a meaningful relationship.

There is a Chinese proverb I have learned through yoga: "Tension is who you think you should be. Relaxation is who you are."

- Spirituality: Much more than religion

For many years I couldn’t pursue my spirituality, after the very word was tainted by the Kabbalah Centre. My spirituality began when I defined it for myself as the opposite of materialism. I was trying to shift away from materialism, consumerism, and greed, and I needed to find a name for this journey.

Mind and body: Yoga connects the psyche with the physical to create a form of spirituality, says Haski-Leventhal.

I am not a materialistic person. Music, spending time with the people I love, and being in nature bring me more joy than shopping and consumables. I needed a term for this preference and decided to call it spirituality.

Steering away from ideas of the soul and God, I then examined the connection between body and mind. There is enough empirical data to illuminate the relationshp between our emotions and thoughts and how our bodies function.

I saw this connection when I started practising yoga. The psyche is strongly related to the physical, and when ignored for too long this connection starts to weaken. On the other hand, practising yoga, music, and nature walks can strengthen it.

- Consciousness: Raising awareness

To have an impact is to be conscious of what is occurring in the world. While the concept of mindfulness might have become a little devalued, it is an essential, often overlooked, aspect of consciousness.

People today spend time eating, watching Netflix, and doomscrolling, all at the same. We believe we are good at multi-tasking, but really we are only good at being distracted.

So many of us have lost the capacity to just enjoy a meal, focusing on the food and its taste, without gazing at our phones. Learning to remove such distraction and be fully present and mindful of where we are, what we are doing, and how we feel is crucial in developing awareness.

People who do their work with mindfulness and consciousness tend to find ways to take joy in what theydo. They are engaged employees and happier human beings.

- Gratitude: Being thankful even for the bad things

A person grateful for their work and life tends to mentor others more, help a peer in distress, or be more focused on making sure customers are happy.

Good pay and other tangible incentives have short-term impacts on employee gratitude; long-term gratitude arises from an alignment of purpose, the chance to bring your true self to work – and, of course, finding your job meaningful.

Pen to paper: Even if thank-you letters are never sent, the positive impact of the act of writing them lives on, Professor Haski-Leventhal says.

There are various ways to cultivate gratefulness. Gratitude journals have become popular: people spending the last hour of their day reflecting on what they have. Writing down three moments of joy each day also has a healing effect. Write thank-you letters to people who matter in your life. Even if they are not sent, the positive impact remains.

The purest form of gratitude is when you learn to be glad about what did not go as planned, for failures and adversities. Misfortune can still hold benefits, even if these are revealed to us years later. While we can still grieve for failure, loss, and trauma, the healing begins when we create positive outcomes out of them and become thankful for them.

- Choice: Some freedoms always exist

Our freedom to choose and the motivations for our choices are crucial for our sense of meaningfulness. If someone has no choice, we don’t ask why they did what they did. We cannot speak of motivations, drives, needs, purpose, or values. We don’t talk about the meaning of actions.

Not always but most of the time we do have a choice, as minor as it may be. Victor Frankl wrote A Man’s Search of Meaning after coming out from Auschwitz back to life. When the Nazis took everything away from him – his dignity, his loved ones, even his food and shoes – he could still choose what kind of human to be.

- MQ Life: Greek field trip offers students archaeology adventure and job-ready skills

- MQ Life: How musical dreams turn into jobs

To derive meaning in life and work, we need to reflect on our past, present, and future choices and ensure that from now on, we choose to act according to our purpose and values.

As the great empathetic English teacher in the 2017 film Wonder said (quoting the American philosopher Dr Wayne W. Dyer): "When given the choice between being right and being kind, choose kind."

- Optimism: Hoping against hope

Optimism is not just a trait or a developed skill, it is a responsibility. Without it, we cannot speak of personal or corporate responsibility, because if we don't believe in our ability to overcome existing challenges and make a difference, we would not take the first step to improve our surroundings and the world.

Greta Thunberg was so worries about climate change that she stopped speaking for years. It took such courage and optimism for her to start a one-person strike in front of the Swedish parliment. Millions now follow her based on their trust that things can change for the better. As with choice, if we believe that everything is out of our hands and we are doomed, then we are.

One essential aspect of optimism is hope, a wish for good results despite the odds not being so great. Research shows that individual with greater hope appear to experience greater success in accomplishing their goals.

Debbie Haski-Leventhal is Professor of Management at Macquarie Business School, the MBA Course Director, co-chair of MQ Inclusion and the author of Make it Meaningful, which will launch at Ryde Library on February 9, 2023.