A 15-year-old at the family dinner table declares she doesn’t need to know the times tables off by heart – she has a smart phone to do those calculations for her.

Pen and paper rock: Literacy lecturer Dr Ruth French says both printing and cursive help students remember information better than keyboard notetaking.

The 11-year-old sitting beside her declares he doesn’t need to know cursive writing, given his teachers have been shrugging their shoulders at this gap in his learning since his Year 3 teacher failed to introduce it. And to be fair, the death of cursive writing has long been forecast in the age of the keyboard.

But education academics disagree with arguments that these fundamental skills are largely redundant in the digital era. And they are backed up by the NSW primary school curriculum.

Lifelong struggle ahead without tables

“We’d like all students going to high school to know their times tables,” says Susan Busatto, a maths education lecturer and former senior NSW curriculum adviser.

“Times tables are a fundamental building block; if children don’t know their times tables they are going to struggle continuously.

“Learning multiplication facts frees up mental space so that children can move on to problem solving, because if you’re going to spend a lot of your time in the classroom number-crunching, you will never get to work with the actual problem.”

Remember more with handwritten notes

Dr Ruth French, a lecturer in literacy education at Macquarie, points to the cognitive benefits of learning to hand write, whether it’s printing or cursive. She also highlights studies that show how prevalent handwriting remains in primary school classrooms, and also how note-taking using pen and paper, as opposed to keyboard, results in better processing and retention of information.

“The NSW syllabus still considers cursive a necessary skill,” French says. “Manuscript (printing) is taught from kindergarten, and cursive from stage 2, or Year 3.

“Why we teach cursive is if people are fluent in cursive and manuscript, cursive is faster – and there is still a benefit in having fluent cursive handwriting for when you want to write reasonably quickly.”

Learning off-by-heart still has a place

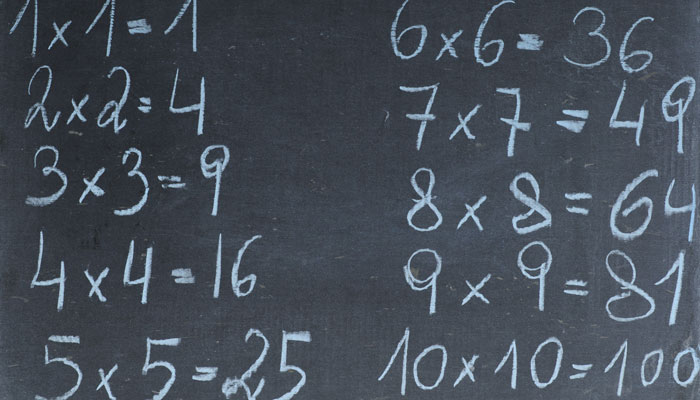

Under the NSW K-6 Mathematics Syllabus, children are expected to know their times tables up to 10 x 10 by Year 6, although many children still learn them up to 12 x 12, Busatto says. Students should also know what the tables mean and how they work. However, the syllabus does not tell teachers how they should teach this; rather, Busatto says, teachers provide a range of ways to help their students learn their tables.

Auto pilot: Practicing constantly through song, apps or the internet helps achieve automaticity which in turn aids problem solving in higher maths, says Busatto.

“There’s an actual suite of ways to learn times tables, ideally children will latch on to the one that works best for them,” Busatto says.

“We want all our students to grasp mathematical concepts, we don’t want them to apply facts without understanding, so we teach multiplication in terms of groupings; for instance we don’t want students just to know that 3 x 4 equals 12, we want them to also understand that 3 x 4 is three groups of four, which gives you the same as four groups of three, so students can visually see what the multiplication fact means.”

Busatto says that while some teachers frown on times table learning by rote, “I think secretly all teachers just wish that their students knew their tables off by heart because they have their place – and some children love their rote, they love knowing them inside and out, upside down, backwards and forwards, they’re not satisfied until they get them all.”

The responsibility, Busatto points out, also lies with students to make sure they know their tables, and the more they practice them, be it through song or the internet or apps, the more likely they are to achieve automaticity and to see the mathematical patterns.

“The really important connection for students to make is that they aren’t learning 144 different facts, it’s only half, because one half of tables is just the other half back to front,” Busatto says.

“Some students think ‘I don’t need to know them, because I’ve got a calculator’, or ‘I’ve got my phone and I’ve always got my phone,’ so I think our students also have to take some responsibility for not knowing their times tables; because, unless there’s a developmental delay, there really isn’t any reason you can’t learn them.”

How handwriting is better for your brain than typing

Dr Ruth French says that while the teaching of cursive writing remains a requirement, keyboarding has also been incorporated into the primary school curriculum.

It’s a far cry from just a few decades ago, when typing was a high school elective taken up by girls with an eye on a secretarial future. “There were families that would have discouraged their daughters from doing it because that wouldn‘t be their job, but these days keyboarding is a universal expectation,” French says.

However, research shows that a lot of regular primary school classroom time – more than 80 minutes a day – is still spent using a writing implement and paper. And while exams may one day be done by keyboard – or even via voice recognition technology – the cognitive benefits of learning to hand write are not going to go away.

“The key cognitive benefit is around the depth of processing of what you’re learning about letters and letter formation as you learn to hand write them,” French says.

“For children who are learning to write, if they were simply to use a keyboard, all that’s required is just perceiving the shape of a letter and touching it.

“When you learn to hand write it, you’re co-ordinating a whole lot of motor and sensory activity, so you’re thinking about how to shape that letter in a way that involves more cognitive processing than just visual perception.”

Learning to form letters properly also helps children when it comes time for cursive - and being able to write confidently by hand also has cognitive benefits over and above the ability to type fast.

The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard, a 2014 US study by academics from Princeton and UCLA, found that students who took handwritten lecture notes got less down than students typing notes into computers, but had better recall of the lecture and did better in subsequent tests.

“They seem to have processed and remembered the information more effectively,” French says.

- Toddlers in child care need rich conversation: new study

- Meet Elias, tri-lingual at three

- Children who have music lessons are quick learners

“If you’re behaving like a Hansard reporter and trying to get down every single word, the actual cognitive processing of the content is a distraction from that. If you handwrite your lecture notes, you’re having to think more deeply about what you’re writing down, to process what are the main points as you go, because you physically can’t write fast enough.”

French says that ultimately there will be a range of choices about how to compose written texts that would have been unimagined in the 19th century, when cursive writing’s main purpose, in those pre-ballpoint-pen days,was to avoid ink blots from lifting the pen.

“My question around the future of cursive would be, do you want to take away those choices? I like having a range of choices,” French says.

“We don’t want to be just the subject of technology and dependent on it for everything. We want to be able to scribble a note on a post-it note when we’re on a telephone, and not have to open our computer first.”