Brazen Hussies tells the story of a group of women who changed Australia. Directed by Catherine Dwyer and just released in cinemas, it is full of rich (and often funny) archival footage and interviews with the women who were on the frontline of the women's liberation movement.

Between 1965 and 1975, the women’s movement secured new political, legal and social rights for women – from the right to drink in public bars to improved access to child care. Women’s movement activists initiated a transformation in gender relations. Yet, as the film makes clear, the fight for women’s rights is far from over: much remains to be done.

Here are five issues that we still need to tackle:

1. Valuing women’s care work

As women moved into the paid workforce in larger numbers from the late 1960s onwards, they left a ‘care gap’ (both in the care of children and the elderly) that has exposed deep-seated gender inequalities.

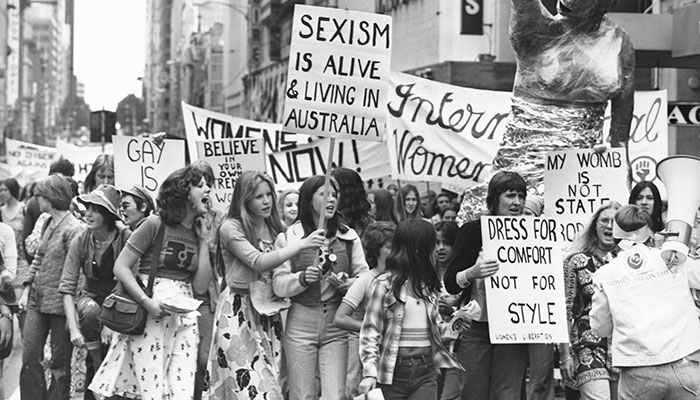

See us, hear us: Women march for their rights in Sydney on International Women's Day in 1975. Photo credit: Anne Roberts, courtesy of Mitchell Library and Search Foundation, supplied by Brazen Hussies.

Women still do the majority of care work (child care, elder care and housework). Even worse, we have long undervalued the work of caring for others, partly because this work has, historically, been done by women.

The feminist economist Marilyn Waring pointed out in her book Counting for Nothing that because women’s caring work is not counted in the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), it has no economic ‘value’.

Worse still, this attitude has attached itself to paid care work: women comprise approximately 85 per cent of Australia’s care workforce, according to a 2019 OECD study, but many of these (female) workers are among our lowest paid, while childcare and aged care operators make significant profits from these women’s labour.

We need to start demanding that men share the care burden far more equally.

This is a long way from free childcare, which was one of the founding demands of the women’s liberation movement in Australia.

The federal government briefly offered free childcare to Australian families at the height of the pandemic in April this year, ending it in early July. While far from perfect, this period of free childcare was evidence that, with sufficient political will, the impossible becomes possible.

We need to hold onto this sense of possibility as we move into the post-pandemic world, but we also need to fight to better reward those who do the hard work of caring for others. And we need to start demanding that men share the care burden far more equally.

2. Domestic violence

Women and children have the right to remain safe in their homes, but women remain far more likely to be subject to violence or coercive control by current or former intimate partners.

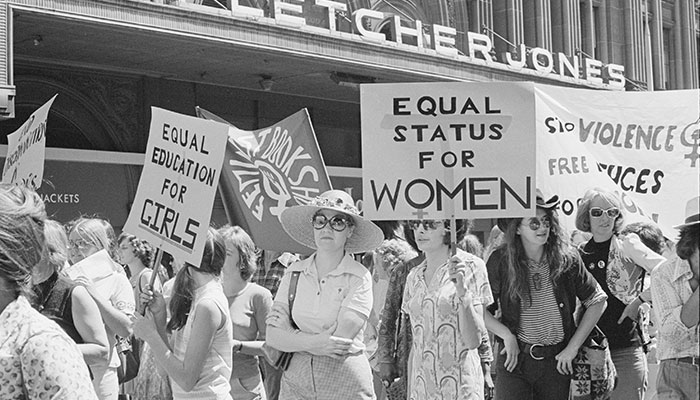

Angry women: An anti-rape rally in Perth in 1976. Photo credit: Amanda George, supplied by Brazen Hussies.

According to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey (2016), one in six women have experienced physical violence by a partner. When we include emotional abuse, it is estimated that 1 in 3 women have experienced such violence.

How to tackle this huge problem?

Better funding for women’s refuges (an innovation of the women’s movement in the 1970s) and community legal centres would be a great start.

We need to respond to domestic violence the way we responded to smoking: as a public health crisis.

But many government plans to combat gender violence depend on long term change in gender attitudes – a process that might take generations to see real results.

According to journalist Jess Hill, author of the must-read book on this subject, See What you Made Me Do, we need to respond to domestic violence the way we responded to smoking: as a public health crisis.

Australia’s public health innovations (including plain packaging of cigarettes) have significantly lowered our smoking rates. Gender violence is an equally urgent problem: Hill argues that we need to treat it that way to see real change.

3. Recognising and valuing diversity

Brazen Hussies does not paper over the differences between women in the women’s movement, and it features Indigenous women like Pat O’Shane and Lilla Watson who point out that the women’s movement was often racist, and tended to privilege the concerns of White women over those of Indigenous women.

While the women’s movement was not as white or as single-minded as it is sometimes portrayed, neither was it as welcoming of difference as it might have been, and it didn’t always grasp the intersectional nature of the oppression experienced by Indigenous women, in particular.

The women’s movement today is still at times guilty of foregrounding the needs of White, middle-class women.

By insisting that they represented all women, the women’s movement often failed to recognise the distinctive needs of Indigenous women, women from migrant backgrounds, or lesbian and queer women.

The women’s movement today is still at times guilty of foregrounding the needs of White, middle-class women: the public faces of feminism in Australia are still overwhelmingly white.

- I quit sugar: making biofactories that run on waste

- Report shows ongoing cyber threats to government websites

However, I see reasons for optimism for a more inclusive women’s movement in Australia: the widespread support for same-sex marriage in Australia, the huge crowds for Black Lives Matter marches this year, the emergence of trans rights activists, and growing awareness that a 21st-century women’s movement needs to find spaces for many voices, and many perspectives.

4. Women’s financial security

When Zelda D’Aprano chained herself to the Commonwealth Building in 1969 to protest women’s unequal rates of pay, I’m sure she didn’t imagine that women would still be struggling to achieve equal pay more than 50 years later.

Equal-pay pioneer: More than 50 years after Zelda D'Aprano chained herself to the Commonwealth Building in Spring Street, Melbourne, women still earn less than men. Photo credit: Courtesy of the D'Aprano family, supplied by Brazen Hussies.

But sadly, women still earn less than men: in 2020, women earned, on average, $250 a week less than men, a gender pay gap of 14 per cent. Women are more likely to take time away from the paid workforce to care for children, and they are also more likely to be clustered in part-time, casual and low-paid work.

All of this has a long-term impact on their financial security: women retire with around half the superannuation of their male counterparts, and if you are over 60 and single, you are more likely to live in poverty than any other family group, according to HILDA data.

Indeed, recent research has shown that more than 400,000 women aged over 45 are at risk of homelessness in Australia. This means that, statistically, many women of the Brazen Hussies generation look set to retire in poverty.

While better financial literacy for women is one part of the solution to this problem, we also need to repair our social welfare safety net to better protect older women from poverty and homelessness, and to recognise the ways that the gendered nature of our wage and welfare systems can perpetuate inequality.

5. Writing (and knowing) feminist history

In the opening montage of Brazen Hussies, filmmaker and activist Margot Nash remarks: "History has to be told over and over again." She’s right: understanding history can help us imagine new possibilities for our future.

Feminist heroine: Elizabeth Reid, Australia's first government Women's Adviser, with then prime minister Gough Whitlam ... Brazen Hussies features women who deserve to be better known. Photo credit: ABC Library Sales, supplied by Brazen Hussies.

However, the history of women’s liberation in Australia is not nearly as well-known by the general public as other aspects of our past: it’s generally not the subject of the kind of history books you can find at airport bookshops, for example.

Brazen Hussies will bring the history of Australian women’s liberation to new audiences. This is crucial for a few reasons: contemporary activists need to understand the struggles of the past in order to build on them for the future, rather than reinventing the wheel.

- New Macquarie research could help slow aggressive breast cancer

- New front opens in Australia's fight to save the koalas

Their stories are a reminder that while second-wave activists achieved so much, some of what they worked for has been wound back or curtailed: we need to be clear-headed about why this was the case as we work to make new gains.

Finally, this is a history filled with feisty, stroppy women who deserve to be better known in Australia. A few weeks ago, Americans mourned the death of the iconic feminist, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, aka ‘The Notorious RBG’.

Australia has its own feminist heroines, as Brazen Hussies amply demonstrates: it would be great to see some of these women on T-shirts and memes, too.

Michelle Arrow (pictured) is Professor in Modern History at Macquarie University. She consulted on Brazen Hussies and is the author of three books, including The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia (2019), which was awarded the 2020 Ernest Scott Prize for history and was shortlisted for the Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction in the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. In 2020, she was awarded a Special Research Initiative grant from the Australian Research Council for her next project, a biography of the writer, feminist and broadcaster Anne Deveson.