The cultural critic: Anthony Lambert

The cultural impact of the moon landing is all around us, forever a reminder of spectacular possibilities.

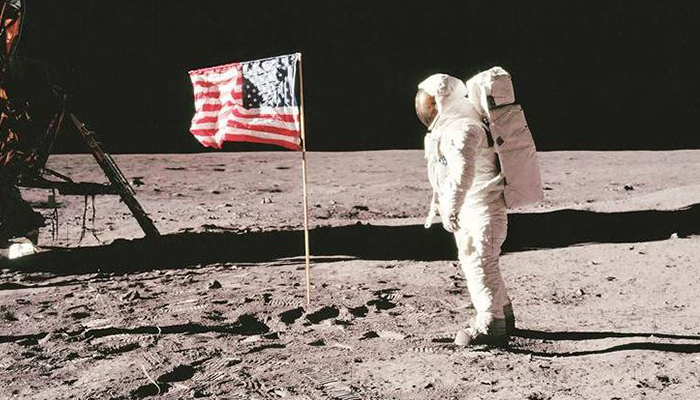

Mankind's giant leap: Neil Armstrong became the first human to walk on the Moon on 20 July 1969. Pic credit: NASA.

Spectacles are large events that demand universal focus, and they have the power to fixate and transform cultures. In the sitcom Big Bang Theory, the science geeks direct a laser onto a retro-reflector left by Neil Armstrong on the surface of the moon. Leonard exclaims “Don't you see what we've done? It's the only definitive proof that there are man-made objects on the moon placed there by a species that only 60 years before had just invented the airplane.” They have connected with something spectacular.

The landing of Apollo 11 on the surface of the moon on 20 July 1969 was, quite simply, the biggest thing that had ever happened. EVER. And it may well still be. For scholars of visual media and cultural studies, interest is in how the spectacle of the moon landing works, with respect to America and the global mediascape in the late 1960s, and the ongoing effects of the spectacle on culture and representation in our contemporary lives.

The moon landing has offered a visual architecture of the modern spectacle. In the CNN documentary Apollo 11 (2019), unseen footage reveals the visual motifs, cues and tropes that have informed films and stories over the past half-century, including the 12-part HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon (1998), and the 1996 Apollo 11 docudrama, which followed from the Apollo 13 film made in 1995, starring Tom Hanks. The 2019 documentary enlivens the ‘real footage’ by reproducing the actual moon landing in high-resolution digital scans that are fully immersive.

The landing of Apollo 11 on the surface of the moon on 20 July 20 1969 was, quite simply, the biggest thing that had ever happened. EVER. And it may well still be.

Whilst numerous other popular documentaries and feature films have been made, including the dramatic First Man (2018) and the Australian comedy The Dish (2000), the cultural impact of the event also lies in its easy incorporation into the stories and images of popular programs and film franchises: TV shows such as Futurama, Dr Who, and Timeless, as well as the Men in Black and Transformers films have all used aspects of the moon landing story as part of larger stories about science, fantasy, good and evil.

The large-scale media coverage of the original achievement managed the world’s attention through distraction from the Vietnam War, and the culmination of the ‘space race’, which offered a celebratory account of American/Western human and technological development. In recent film and television from Big Bang Theory to First Man, the moon landing continues to powerfully inform representations of humanity, space, the world and the universe.

The event lives on through what is repeated and circulated in popular culture – not only as the measure of achievement but as the postmodern reminder of spectacular possibilities.

Dr Anthony Lambert is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University.

The planetary scientist: Craig O'Neill

The Apollo mission transformed our understanding of our own planet.

Rocky route: Apollo 11 carried the first geologic samples from the Moon back to Earth, including 50 rocks. Pic credit: NASA.

In 2002 I was lucky enough to have dinner with an Apollo-17 astronaut, Harrison 'Jack' Schmitt – the only scientist ever to walk on the moon, and a geologist. Dr Schmitt was giving a public lecture at Sydney University, and as a geoscience grad student studying planets, I scored an invite. As the only other earth scientist, the organisers sat me next to Harrison - a terrible idea for the rest of the table, as we proceeded to talk about rocks for the next three hours.

Harrison's experience on the Apollo program is a point of pride in the earth science community – the true skill required for a scientist on the ground in an alien environment isn't astronomy. It's geology. And nowhere have the Apollo missions cast a longer shadow than in the earth sciences.

The Apollo missions were a turning point for planetary science ... the samples have powered 50 years of science and continue to be worked on today.

The Apollo mission samples showed that Earth and moon came from the same body. The isotope signatures of both – the "DNA" of rocks – are uncannily similar. However, the moon had some major differences. It was very dry, had a very small core, and much of the crust was an unusual rock rich in a mineral called feldspar.

Together these observations led to a model for the formation of the Earth-moon system via a giant impact, where a Mars-sized object hit the growing Earth, ejecting material to eventually form the moon.

The moon's surface is also very old. Most of Earth's earliest record has been destroyed, yet the moon provides a time-capsule of this period. It showed that the early moon, and by inference the Earth, started life mostly molten, covered by deep "magma oceans". The Apollo samples allowed us to date the epic impact craters forming at the time, and constrain the flux of asteroid impactors bombarding the early solar system. Soon after this period ended, evidence for life appears on Earth, which may have had to wait until these ocean-vaporising impacts ceased.

The Apollo missions were a turning point for planetary science. Previously accessible only by astronomy, planetary bodies were now accessible to missions, and sample return - and thus the whole arsenal of analytical tools geochemistry could bring to bear. The Apollo samples have powered 50 years of science, and continue to be worked on today.

It's been a long time since Harrison Schmitt, with Eugene Cernan, were the last humans to walk on the moon, and we are long overdue for a new generation of scientists to follow in their footsteps.

Associate Professor Craig O’Neill is Director of the Planetary Research Centre at Macquarie.

The historian: Chris Dixon

The moon landing showed the world what political will can achieve. Today, humanity urgently needs to find that will again.

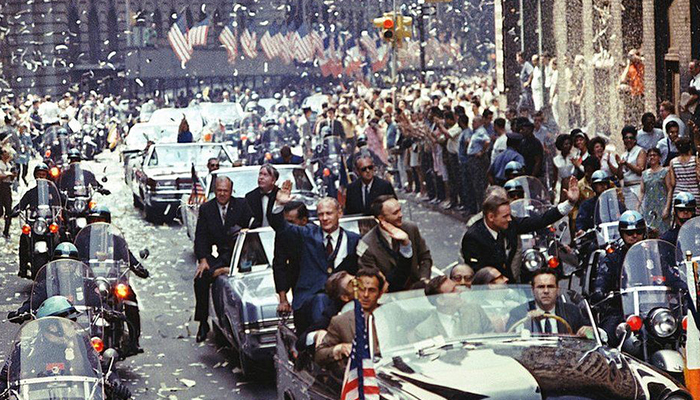

Mission milestone: The moon landing was a huge moment in US and world history and became a cause for national celebration like this New York parade for the returned Apollo 11 crew Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins and Neil Armstrong. Pic credit: NASA.

The moon landing did not transform life on Earth. Yet it was a moment of profound historical significance. Coming near the end of a decade in which Americans had spent as much energy fighting themselves as they had expended in an ultimately unwinnable war in the jungles and rice paddies of faraway Vietnam, many Americans saw the success of July 1969 as a reassuring sign that the United States still had the right stuff. While some were contending that America in the 1960s was a generation lost in space, the moon landing suggested there was, perhaps, still time left to start again.

Of course, the moon landing was much more than an American moment. The grainy black-and-white TV image of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon represented a transcendent, unifying moment. This was not just an American triumph, but a sign that all peoples, regardless of nation, race, or faith, were inhabitants of the same precarious planet.

Amid the technological triumphalism and soaring rhetoric associated with the moon landing, it is often forgotten that President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 pronouncement that the United States would put a man on the moon before the end of the decade had not been greeted with universal acclaim. Sceptical of the project’s feasibility, and concerned about its expense, some Americans worried that a failure to reach Kennedy’s ambitious goal might repeat the embarrassment and humiliation that had followed the Soviets’ 1957 launch of Sputnik.

Although the United States sent a further six missions to the moon, Apollo 11 proved a tough act to follow.

Perhaps because the space race was so inseparable from the Cold War, during the 1960s the US government invested vast resources to the quest to reach the moon. Harnessing the best and the brightest of the nation’s scientific minds, the space program demonstrated the positive possibility of large-scale government investment in projects of national and international significance. Even if the public purse permitted, it is doubtful that the United States would today have the political will to invest the resources necessary for such an ambitious exercise.

It is one of the ironies of history that it was Richard Nixon – who had narrowly and contentiously lost to John Kennedy in the 1960 Presidential election – who welcomed the Apollo 11 astronauts back to Earth. Acclaimed as heroes, Armstrong and his fellow crewmembers rode in ticker-tape parades in Chicago and New York City, addressed a joint sitting of the US Congress, and embarked on a world tour that took them to 22 countries.

Although the United States sent a further six missions to the moon, Apollo 11 proved a tough act to follow. Apollo 13 nearly ended in disaster, and by December 1972, when Apollo 17 completed its mission, the trip to the moon had become almost routine, if not passé.

And while Neil Armstrong’s description of “a small step for [a] man, but a giant leap for mankind” highlighted the unbounded optimism of that moment, the decades since have seen the increasing militarization of space and a growing cynicism toward the type of scientific endeavour that made the moon landing possible. As the planet that Armstrong and other astronauts contemplated from afar grapples with the challenge of climate change, it is incumbent on all of use to demand, and generate, the same type of political will that put a man on the moon.

Professor Chris Dixon is Head of the Department of Modern History, Politics and International Relations at Macquarie.

The engineer: Noushin Nasiri

Technology developed during the Apollo Mission has made everyday life easier – and safer.

Fiction to reality: Wireless headsets, cordless tools, swipe cards and memory foam hospital beds are among the NASA inventions now used in everyday household items back on Earth.

The day before the launch of Apollo 11, Ralph Abernathy, civil rights leader, held a sign at the Kennedy Space Centre that read: “$12 a day to feed an astronaut. We could feed a starving child for $8.” The total cost of the Apollo program was $US25.4 billion, more than $US100 billion in today’s money. Fifty years later, some may still wonder if the moon landing was a waste of money, and also may question, like Abernathy, why we spend so much money to explore space when we could be more focused on improving the quality of life of people here on Earth.

From memory foam to wireless headsets, NASA inventions have contributed to improving lives of people on this planet.

The answer, however, is quite complicated as it is difficult to put a value on something of the magnitude of the moon landing. And the reality is that space exploration has brought us numerous benefits. From memory foam to wireless headsets, NASA inventions have contributed to improving lives of people on this planet. The former, which is being used in helmets as well as hospital beds, was created in the 1970s by NASA to absorb the energy of crashes during landing and increase astronauts’ chances of survival. The latter was initially developed to improve the astronauts’ communications while in the spacecraft.

Another example is cordless tools such as the cordless drill, screwdriver and vacuum, which are common in households around the world. Although these tools were generally invented before the moon landing, NASA took away the complications of tangled cords. Through a collaborative project with Black & Decker, NASA made the daily lives of the masses easier by developing these lightweight, battery-powered and portable tools.

The catastrophe also led to new technology. After the three astronauts of Apollo 1, the first crewed mission of the Apollo program, died in a fire in the spacecraft cabin during a launch test, NASA engineers designed and fabricated space suits made of fire-resistant material. That material has since been used in the outfitting of firefighters, race-car drivers and soldiers to help protect their lives in the case of fire.

NASA’s innovations are not limited to hardware technologies, with sophisticated software tools developed by its scientists also changing the lives of millions. One great example is the software they designed to manage complex space systems which later was utilised in developing the swipe-card devices we use every single day.

Fifty years ago, on 20 July, the science fiction fantasy became the reality when Neil Armstrong walked on the surface of the moon; and now, we should be wondering how different life would be without the many NASA technologies that are taken for granted.

Dr Noushin Nasiri is a Lecturer in Materials Engineering at Macquarie’s School of Engineering.