With Greater Sydney in its second lockdown and the rest of the country fighting off an outbreak of the Delta strain, Kevin McCracken, Honorary Associate Professor in Geography and Planning at Macquarie University, says Australia is learning from its COVID-19 lessons – but we are far from the end of this public health crisis.

Crisis: Authorities moved too slowly to declare Sydney's current lockdown, says global health expert Dr Kevin McCracken.

In a new book exploring the international experience of COVID-19, Dr Kevin McCracken, an expert on global health who wrote the chapter on Australia, warned that the greatest threat to conquering COVID-19 in this country “could in fact prove to be complacency towards the virus”.

“There have been numerous worrying signs of this,” he wrote. “The bewildering reluctance of most people to wear protective masks on crowded public transport or in shopping centres, etc, being only the visually most obvious.

“Time will tell. For now, the COVID-19 story, both in Australia and globally, has a considerable distance to travel.”

We have had that silly vaccine hesitancy, but I think that’s taken a bit of a knock in the past couple of weeks.

McCracken finished the chapter – a comprehensive summary and commentary of Australia’s pandemic experience – last October, but those final paragraphs have proved prescient.

The seeding of the latest outbreak from a limousine driver who was unvaccinated when driving international flight crews around, prompted warnings against complacency from authorities – warnings that continue to be made daily during the current lockdown.

“It seemed a major oversight by whoever drafted the new restrictions; what seemed an obvious thing got overlooked,” says McCracken.

“When you think about that particular episode, and now what we have on our hands, it can take off like wildfire and any complacency will hopefully be disappearing pretty quickly.”

Too slow to vaccinate

McCracken says there has also been an element of complacency in the vaccine hesitancy that has contributed to Australia having one of the worst vaccination rates in the world.

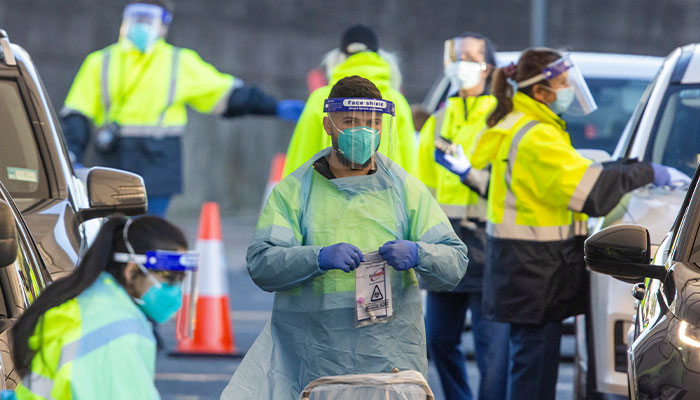

Action: Queues at the NSW Vaccination Centre in Homebush on July 1 ... McCracken believes vaccine hesitancy may have taken a knock.

However, anecdotally at least, Australians appear much more willing to wear masks as this latest coronavirus crisis embroils the nation.

“We have had that silly vaccine hesitancy, but I think that’s taken a bit of a knock in the past couple of weeks,” McCracken says.

“Certainly where there is an outbreak it makes people think more seriously about doing something sensible. People are starting to appreciate that this can take off and get out of control very, very easily.”

You would hope that the lessons have been learned, although the pessimist part of me suggests that no, there could be other disasters like these.

He believes the NSW government could have moved faster to impose the current lockdown.

“I can partly understand the reluctance to go into lockdowns – politicians are trying to balance two crises, economic and health,” he says.

“Personally, I think lockdowns are a necessary part of the armoury against it, but then again when you don’t own a little café or a shop it’s not your livelihood going down the drain.

“But I would give primacy to actions to protect health and get rid of the viral problem, and that is going to involve a lot of pain for a lot of people; it already has, but hopefully you get the rewards for going in sharp and hard.”

Mistakes and painful lessons

McCracken’s work is featured in Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreaks, Environment and Human Behaviour, released in May this year by the prestigious international publisher Springer.

Blunder: The Ruby Princess disembarkation error was among the shocking low points of Australia's COVID-19 response.

The book includes more than 24 country case studies from across Asia, the Americas, Europe, Africa and the Pacific Islands. McCracken’s chapter is simply entitled COVID-19: The Australian Experience.

It describes the COVID-19 outbreak as “indisputably” one of the country’s greatest ever health crises, while pointing out that by comparison with most countries, Australia’s population – with 900 deaths and 27,000 positive cases as of October last year – has survived well.

“In terms of deaths, the outbreak falls a good deal short of the 1919 Spanish Flu toll (the usual comparative pandemic yardstick) of around 15,000 deaths Australia-wide,” he writes, but in terms of disruption to life has been enormous.

For many, the most unedifying memory of the pandemic will be the aggressive widespread panic buying of food early in the outbreak.

The comparatively low tally is despite “mistakes and painful lessons” in pandemic preparedness, planning and management, McCracken writes.

How could we forget the Ruby Princess ship disembarkation error which led to 28 deaths; the tragedy at Newmarch House where 19 aged-care residents died; and the Melbourne hotel quarantine debacle, which seeded Victoria’s second wave – all shocking nadirs in Australia’s COVID-19 experience that are described by McCracken in his chapter. Foolhardy breaking of gazetted public health regulations by small numbers of individuals have also been costly.

“You would hope that the lessons have been learned, although the pessimist part of me suggests that no, there could be other disasters like these,” McCracken tells the Lighthouse. “Hopefully there won’t be, but I am not totally confident.”

Living in a pandemic

McCracken’s summary of Australia’s experience ranges across the hardest-hit members of Australian society: the tens of thousands who lost their jobs; the women and children exposed to domestic violence; the Asian Australians subject to racial vilification; and the frontline health and aged care workers at special risk of contracting the virus.

On the frontline: Health-care workers have been among the groups at special risk of contracting the virus.

He plots the nation’s political journey, from the setting aside during the pandemic’s early months of customary political confrontationalism for a united national approach, to the eventual re-assertion of partisan divides and disagreements between states and the Commonwealth.

But for many, McCracken writes, “the most unedifying memory of the pandemic will be the aggressive widespread panic buying of food early in the outbreak, supermarket aisles being stripped of toilet paper, tissues, pasta and tinned foods.”

Even with the amazing development of vaccines in such a short time frame and their promise of so-called “herd immunity”, McCracken believes life may never return to exactly how we knew it.

Regardless, borders must reopen at some point – "our wellbeing as a nation depends on it" – although it mustn’t happen too soon: “There is a world out there that doesn’t have COVID quite as under control as we do here in Australia,” he says.

Meanwhile, those final paragraphs of his chapter, he says, still very much stand.

“The COVID story in Australia still has a long way to go; anyone who thinks otherwise is being a bit naïve.

“People talk about returning to a normal life, but I am not too sure what normal is going to be in the future – our lives have changed and we have to accept that.

“I think COVID is going to be part of our lives from here on in; I don’t think it is realistic to think it will ever be totally eradicated.”

Dr Kevin McCracken is Honorary Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Planning at Macquarie University, and co-author of Global Health: An Introduction to Current and Future Trends, Routledge, London.