An intriguing tale takes place in Cleopatra’s Egypt, set around a secret society called the Order of Ancients, plotting to control the throne. The story involves abductions, murders and battles, and the main characters must decipher messages and codes hidden in hieroglyphics.

Hidden messages: The hieroglyphics from the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan, Egypt, were used to build a tool that will helps scholars and students translate stories dating back thousands of years. benihassan.com

Welcome to Assassin’s Creed Origins, the tenth episode in Ubisoft’s blockbuster role-play video game series, hailed for its realistic scene setting and engaging gameplay.

The designers engaged experts so they could include genuine hieroglyphics in the gameplay – and found it was a painstaking process.

“While working on the game with Egyptologists, we’ve realised how difficult it is to unlock the secrets of that time,” says Ubisoft Project co-ordinator, Pierre Miazga.

The Rosetta Stone, captured in 1799 during Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, was key to deciphering hieroglyphs; but that slow process has not changed much in over 200 years.

- Let's get that bread: How teenagers change language

- Mystery of stolen Egyptian artefact cracked by hieroglyphs

Ubisoft decided to use their expertise to help create a machine learning tool to translate ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs, and last year launched The Hieroglyphics Initiative, and put out an international call for scholars to help.

“We became convinced that we had our part to play in research efforts, putting our know-how and resources to History’s best interest,” Miazga explains.

Macquarie's experts heed the call

For Dr Alexandra Woods, a senior Egyptology lecturer at Macquarie, the project offered a great opportunity to build on existing Macquarie research. She’s been developing a website to showcase the tombs at Beni Hassan in Egypt since 2016.

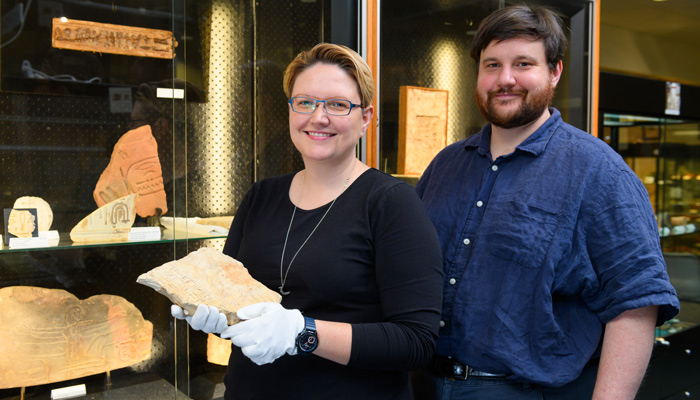

The Hieroglyphics Initiative: Dr Alex Woods and Dr Brian Ballsun-Stanton worked with game developers using Macquarie's extensive digital assets from Beni Hassan.

“Ubisoft's Hieroglyphics Initiative is developing a machine learning based tool – the Workbench Tool - that will create a clear workflow to process images of hieroglyphs, identify signs and translate the glyphs, a bit like Google Translate does,” explains Dr Woods.

Macquarie’s Department of Ancient History signed up as Principal Academic Partner for The Hieroglyphics Initiative and Dr Woods and Macquarie data architect Dr Brian Ballsun-Stanton have spent the past six months working with Ubisoft’s developers Psycle, to help create the Workbench tool.

Using Beni Hassan’s images to teach computers how to decode hieroglyphs

Psycle have been given access to the extensive digital assets that Macquarie’s team has assembled, images and translations of the brilliantly-coloured pictures and inscriptions adorning the rock-cut tombs of the Beni Hassan site in Egypt’s Nile Valley, which tell the stories of daily life in Egypt dating as far back as five thousand years.

There was particular focus on the tomb of Khnumhotep II, says Dr Woods. “This tomb was featured as it is one of the most famous and remarkably well-preserved examples from the Middle Kingdom period,” she explains.

“The tomb contains incredibly rich and detailed inscriptional material with a range of methods of carving as the hieroglyphs are carved in sunk relief, incised or painted with precise detail,” she adds.

- Death metal music and violence do not go hand-in-hand: study

- Internet download speed rockets to 10 gigabytes per second using 'magic' chip

Psycle has used various photographs from the tomb to test their process tool, which creates line drawings from a photo, and their auto-classifier tool, so it can "learn" to read and recognise the symbols.

The Workbench tool then analyses the hieroglyphs by identifying the signs according to the discipline's hieroglyphic sign list, parses the sentence and translates the inscription using an online dictionary.

Along with the data, Psycle taps into the expertise of Dr Woods and Dr Ballsun-Stanton.

Experts in their fields: Woods works in Egypt as an epigrapher studying ancient inscriptions, while data-scientist Ballsun-Stanton is the link between game developers and scholars.

“We meet weekly to provide detailed feedback on the Workbench tool, and how it might be used in research and educational settings,” says Dr Woods.

For the past 15 years or so, Dr Woods has been doing archaeological fieldwork in Egypt as an epigrapher – an expert on ancient Egyptian tomb imagery and inscriptions. She’s worked at some famous sites including Saqqara, Deir el-Gebrawi, Meir, Tehna and most recently Beni Hassan – and has also taught students the slow and painstaking process of hieroglyphics translation.

As a data scientist and digital humanities expert, Dr Ballsun-Stanton has been the link between the developers’ highly technical work, and the pragmatics of making the tool useful for scholars.

“I’ve been advising them on how the tool models data and the most appropriate ways that the tool can be used,” says Dr Ballsun-Stanton.

Digitising Beni Hassan

Macquarie University’s research team has been exploring the site of Beni Hassan since Professor Naguib Kanawati’s first expedition there in 2009, and in 2016 began an Australian Research Council Discovery Project to better understand the imagery in the tombs and develop a digital showcase of the ancient site.

“The educational potential for this kind of material is mind-blowing."

The team has developed a website, https://benihassan.com/ - which explores the purpose of the brightly-coloured art and writings at the tomb site of Beni Hassan, depicting battles, hunting and the daily life of regional Egyptian rulers over 3,000 years ago.

“The educational potential for this kind of material is mind-blowing,” Dr Woods says. “Rather than a dry story about life in antiquity, the images in the tombs can bring these ancient lives, experiences and stories to life, capturing the imagination of students and giving them access to this cultural heritage that may well be under threat in future generations.”

The ARC Discovery Project is a collaboration between Macquarie and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Team members include Professor Naguib Kanawati, Dr Linda Evans, Dr Janice Kamrin (from the Metropolitan Museum) and Dr Woods.

Future work could involve a full 3D scan of the site, with academic commentary and explanatory material.

Remarkably preserved: This excerpt from the (auto)biography in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan, Egypt, describes how he and his grandfather were appointed by king to rule the region and town Menat-Khufu. Link to benihassan.com

“This work has great potential both for historic sites and for students studying the ancient world in general,” Dr Woods says.

Dr Woods also is the academic lead of the Beni Hassan Research Group, a group of academics and Ancient History students who contribute to the Beni Hassan website, which is a visual dictionary for all inscribed tombs at Beni Hassan.

The Visual Dictionary contains accessible descriptions of the various themes, scenes, details and architectural features in a tomb. It includes translations of the hieroglyphic inscriptions, transliterations (which convert the script into a different character set) and also some transcriptions in Jsesh - a word processor used for Egyptian hieroglyphic texts.

The Dictionary also has high resolution zoomable photographs and line drawings so visitors can discover and explore the various aspects of the tomb at their own pace, according to their own interests.

“The students involved in the project have gained invaluable skills and knowledge by working on a digital humanities project,” says Dr Woods. The students involved were part of a collaborative learning community using a ‘learning in partnership’ methodology, she says.

“They have learned many digital tools and honed their communication skills in synthesising and curating data on ancient Egyptian tombs and making the ancient world accessible to a diverse and global audience,” she says.