There has never been a more interesting time to examine brand communities and consumer reactions than the past year. Barely a week passes without a brand calamity sparked by poorly developed advertising, a complete lack of understanding of consumer perceptions, or a brand faux pas on social media.

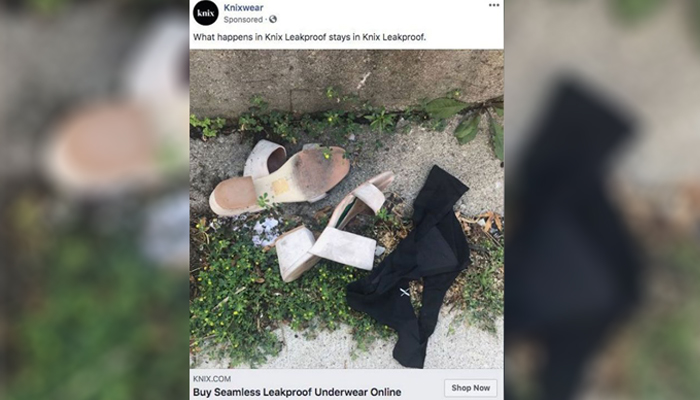

Brand backlash: Knixwear has been slammed over this Facebook ad which many saw as depicting sexual assault.

The latest furore is over Knix, a global underwear brand which champions “all women to live unapologetically free”. It released an ad on Twitter and Facebook showing a pair of black underpants discarded alongside a pair of shoes in what appears to be a dirty, unkept suburban alleyway. The Knix campaign was designed to draw attention to the versatility of women's period-proof underwear – as Knix put it in the ad, 'what happens in leak proof stays in leak proof'.

The ad spawned immediate and widespread backlash and rage among consumers online.

On Twitter one consumer commented: “Hey Knixwear — so, what’s up with this ad that seems to be invoking sexual assault as a side benefit to your underwear?”

Not long after the ad aired, Knix deleted it from their social media accounts. They issued an apology which read in part: “You're absolutely right to be scratching your head as to how this was ever posted in the first place and so we wanted to share some context.

In the highly networked environment that is social media, the mud sticks (and is thrown) for a very, very long time.

“The concept behind the ad was 'what happens in leak proof stays in leak proof'....(pee, sweat, blood) as a parity (sic) on the popular saying What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.

“I can promise you there was no intention to connect our product and brand with sexual assault and violence and that no one within our company would make light of something so serious.

“We are so very sorry. I hope that you will accept our sincere apologies and we cannot thank you enough for flagging this with us.”

Slowdown in sales: Poorly executed ads can cause irreparable damage to a brand, such as being shunned in certain markets, warns Bowden.

However, from a branding perspective, Knix's mealy-mouthed words are all too little too late. In a highly networked social media environment, poor brand decisions like this, which lack both tact and taste, spell sales death spirals for brands.

Worse still, they turn a once positive and benign consumer into a highly activated and motivated justice-seeking warrior, capable of single-handedly spreading negative brand information to an almost limitless social media audience.

Mud sticks. But in the highly networked environment that is social media, the mud sticks (and is thrown) for a very, very long time.

Knix isn't alone as a case in point

H&M recently came under fire after it loaned apparel to The Buro 24/7 a Kazakhstan magazine which featured the brand on a model apparently lying lifeless near a blood-covered knife. Another model was featured laying lifeless on a bed having her stillettos tagged and bagged by forensic scientists.

Consumers reacted swiftly, denouncing the magazine, and indirectly H&M, for eroticising violence against women.

H&M was forced to issue a statement to distance itself from the ad: "It should be noted that H&M is strongly opposed to the romanticisation of violence," said its Russia spokesman Artur Kasimov.

Online fashion giant ASOS sparked outrage last month when it released a keyring labelled “stalker” by a designer called Skinnydip. ASOS was forced to remove the item from their website after an anti-stalking charity tweeted "Hello @ASOS_HeretoHelp, do you also sell ‘RAPIST’ and ‘MURDERER’ keyrings?... after all; 'gals just want to have fun'...”.

Skinnydip also removed the item from its own website following the consumer outcry.

Commercial clampdown: Dolce & Gabbana is still struggling to shake off the fallout from a controversial advertising campaign in China, says Bowden.

In yet another example, and almost a year after the event, the Dolce and Gabbana racism scandal still continues to irk the market. The Italian fashion house featured a Chinese model struggling to eat pizza with chopsticks ahead of a scheduled fashion show. The intensity of consumer vitriol was both swift and palpable and the brand was accused of crossing the racism boundary.

Coupled with apparently incriminating commentary originating from the brand’s co-founder Stefano Gabbana, Dolce and Gabbana were forced to abruptly cancel their fashion show and issue a public apology: “Our Instagram account has been hacked. So has the account of Stefano Gabbana. Our legal office is urgently investigating. We are very sorry for any distress caused by these unauthorised posts. We have nothing but respect for China and the people of China.”

Almost a year later and the brand data provides a telling impact picture. Dolce and Gabbana remains 'cancelled' in China, a market which once made up approximately a third of the brand’s sales. It has been reported that platforms such as Yoox Net-a-Porter and Alibaba have continued to either remove the brand, or limit its stock.

The ongoing banishment of brands in burgeoning luxury markets such as China have the potential to irreparably damage them. Whilst some brand transgressions can be overlooked, others, such as this example, are simply never forgotten.

Negative engagement: Consumer revenge, retaliation and retribution

In marketing terms we call this behaviour negative consumer engagement. Negative engagement captures consumers’ unfavourable brand-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviours during their interactions with brands. Consumers damage brand reputation and value through actions such as negative word-of-mouth, brand switching, avoidance, rejection, retaliation and revenge behaviours.

The very real danger for brands with regard to negative engagement is that paradoxically, negative brand relationships are in fact more common than positive relationships, with an average split across categories of 55 per cent/45 per cent.

Consumer anger can be particularly detrimental as it prompts customers to take punitive actions towards a brand. While many consumers may simply want justice, and for a wrong to be corrected, other consumers may want more.

Revenge-seeking consumers, for example, hold extremely strong, negative emotions towards a brand. These emotions prompt hostile thoughts, malice and brand sabotage.

Anger is contagious. Consumers like the ones who reacted to the Knix campaign can do even more damage to the brand since they actively co-opt others to adopt the same attitudinal and behavioural position towards the brand. We can see this in the commentary on posts when consumers actively encourage others around them to participate.

In brand-fail cases like these, it is not just buyers of the brand that are ultimately affected; the strong emotional aspect of negative consumer contagion carries the risk of ‘spilling over’ to damage other customer segments too.

Serious fashion faux pas: H&M recently faced a backlash after its clothing was used in a Kazakh magazine spread which critics said romanticised violence against women.

Perhaps you saw the Knix brand-fail, and thought to yourself – ‘It doesn’t matter, I don’t buy Knix anyway.’ Well, the problem with negative sentiment is that it is contagious and spreads rather like a virus; one exposure to the brand-fail and you’re likely to ‘catch’ the bug and develop negative perceptions of the brand.

The #Call-out and #Cancel culture

In this regard, 2019 has been an era of 'call out and cancel' culture in response to brand transgressions – consumers are more proactive than ever in voicing their concerns online. They are quick to share their opinions, gang up and jump on the social sentiment bandwagon.

Knix should have refused the siren song of poorly screened and selected cute advertising initiatives when the internal army of creatives came knocking.

Through social media, consumers can activate networks, stir emotions and create an issue-agenda movement. Sharing a cynical meme, commenting on posts, Tweeting, corralling others to a shared position on an issue – these are all ways in which consumers can voice their opinion on social media and be heard.

They are also quick to vote with their keyboards and ‘cancel’ their brand relationships if they feel vexed, which involves boycotting the brand or company. The issue of how ‘big’ the transgression is really is immaterial; it can be real or imagined but either way it involves the consumer withdrawing their attention and affection towards the brand and, in the worst-case scenario, enacting retaliatory behaviours.

So, what is the lesson to be learned?

The key take out from these brand transgression examples is that understanding consumer sentiment is critical. Knix should have refused the siren song of poorly screened and selected cute advertising initiatives when the internal army of creatives came knocking.

There were 60 ads pitched during Knix's internal ad hackathon by its own employees which also begs the question – where was the independent consumer market research? Asking internal employees to develop creative ad ideas has its own in-built dangers and pitfalls. But instead, it rushed ahead with what it believed was a clever and creative ad appeal based on a twist of the idea of 'what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas'.

The upshot? Knix didn’t just damage its own customer market. It damaged its non-customer market for the foreseeable future.

Jana Bowden is Associate Professor, Department of Marketing, Macquarie Business School